This article originally appeared in the American Journal of Roentgenology, written by Dr. Howard Forman, associate editor of health policy for the American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS).

In addition, I have been fortunate to have many guest editors who have brought their own expertise to bear on important topics. In this column, I will bring together two recurring themes: health insurance and the uninsured. I will discuss how tax reform, which is seemingly unrelated, may offer an opportunity for real improvements in our current healthcare system.

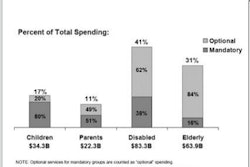

Although expansions of current public programs represent a viable and legitimate option for covering the uninsured, there are many concerns about such solutions. If one were to lower the eligibility age for Medicare, expand the eligibility for Medicaid and the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), or otherwise provide public healthcare to the uninsured, there might be unnecessary inefficiencies introduced.

There is serious concern that such plans could further strain state budgets and the federal budget without necessarily solving the problem. Further, many people already feel that these programs are less than perfect. The alternative is to use the tax code and private sector delivery mechanisms (such as managed-care organizations) to deliver healthcare to the uninsured, in much the same way that they are for large employers.

Recently, Robert Helms, a respected health policy expert at the Washington, DC-based conservative think tank the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, wrote a briefing paper ("Tax Reform and Health Insurance") on this issue. What follows are his recommendations (in italics), followed by my comments on each recommendation.

Efficient reform requires some form of a tax cap as an upper limit on the tax exclusion. For political reasons, this could be set at a relatively high level and moderately indexed so that it becomes more binding over time. While this may be modest in its initial effect, it would send a strong signal to employees, employers, and insurance companies that it is time to get serious about redesigning health insurance coverage and cost-containment policies. Health insurers and employers are beginning to move in this direction by exploring new information systems and new forms of disease management, but a stronger effort by a larger number of employers would speed the process of reform. This kind of reform cannot be done through direct regulation and so must be done through market experimentation to determine the most effective strategies.

In the March 2005 American Journal of Roentgenology (AJR, Vol. 184:3), I addressed this issue. I do believe that we have a considerable impetus to overpurchase healthcare insurance. This is firmly rooted in the tax code of our country and is an unfortunate means of subsidizing the healthcare of the rich at the expense of the poor. Professor Helms is correct in recognizing this issue and more so in realizing the political difficulty of implementing such a change.

Both political parties have a strong stake in maintaining the current limitless exclusion. However, this ultimately means that our federal government is offering a tax subsidy to each individual that is equal to the product of their marginal tax rate and their cost of employer-purchased insurance. It does not take too much of a leap to understand that this offers a much larger subsidy to the higher income (and, thus, higher health benefit and higher marginal tax rate) individuals. In addition, moral hazard is generally higher and inefficiencies are higher with larger benefit packages.

A new program of refundable tax credits could be used to promote the twin objectives of increasing coverage for low-income workers and promoting the growth of market-based insurance. Allowing the credits to be used for the purchase of individual insurance is a necessary condition for efficient market reform. Allowing low-income individuals to use the credits to buy into an employer's group plan, while raising the cost to the federal government, would help to control crowd-out and promote the growth of coverage among the small firms that presently do not offer health coverage. Allowing the credits to be used for a variety of health insurance plans would help to promote a more efficient market than mandating that they be used for HSAs [health savings accounts] alone.

Here, again, Helms is (at least theoretically) correct. This would be an enormous step in the right direction, if (and this is the big "if") the tax credits were set sufficiently high to induce individuals to purchase (or have their employers purchase) health insurance. Further, while Helms is a proponent of HSAs, he acknowledges that this is only one model that may or may not be the best option. This is not a novel approach, but it has never been robustly funded or given sufficient attention by our legislators to make a real difference.

Despite my concerns about singling out HSAs as the only type of health policy worth encouraging, I do believe they have the potential to exert a strong influence on consumers and providers alike to seek both better quality and more cost-effective care. Given the interest they are receiving in the marketplace, they are a target of opportunity. Giving them more favorable treatment among individuals and employers would speed their rate of adoption and their influence on basic incentives. This movement would be even more effective if combined with tax credits to low-income individuals and a limitation on the tax exclusion.

In the May 2005 Policy Brief (AJR, Vol. 184:5), I discussed consumer-directed health plans, including HSAs. I have concerns about the disparate effects that HSAs may have on the chronically or severely ill and the poor in general. As radiologists, we have other concerns about Helms' recommendations. The private sector has typically treated us marginally better than the Medicare and Medicaid programs. There are generally higher administrative hurdles (preauthorization), but also more generous reimbursement (in most locales) with private payers. Thus, Helms' proposal would serve us well, by using this mechanism to expand coverage.

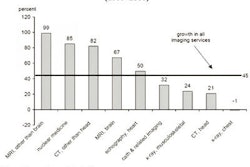

On the other hand, the movement to empower consumers (via HSAs and reduced tax subsidies) would likely reduce the demand for some of our less proven technologies. How you or your particular practice may be affected is likely to be determined by the population you serve and the mix of technologies you use to diagnose and treat your patients.

It is important to recognize the importance of the U.S. tax code in shaping our current healthcare system, and Helms' views could represent a starting point for our representatives as they seek to find a solution to the uninsured problem. For radiologists, the advice remains the same: be invaluable to your patients and your clinicians and you will thrive regardless of what shape our healthcare system is in.

By Dr. Howard P. Forman

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

October 20, 2005

Dr. Forman is associate editor of health policy for the American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS). This article originally appeared in the American Journal of Roentgenology (September 2005, Vol. 185:3). Reprinted by permission of the ARRS.

Related Reading

Medicaid cuts and radiology's quandary, September 13, 2005

MedPAC, Medicare, and imaging growth, August 16, 2005

Medicare's condition in 2005: critical, June 15, 2005

Health benefits at work: what to expect in the future, May 24, 2005

National health expenditures and another year of 'unsustainable growth,' May 4, 2005

Copyright © 2005 American Roentgen Ray Society