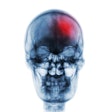

"Bullets, bones, and kidney stones" was a phrase that sprung up in the earliest months of the medical use of x-rays by mostly young U.S. doctors. Just as Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen had noticed that the fundamental x-ray beam he discovered in November 1895 showed bones minus normal flesh, young surgeons found that the images could show them where surgery could correct problems.

On February 3, 1896, John Cox, a McGill University physicist in Montreal, produced an x-ray image of the leg of a young man who had been shot to show a bullet that surgeons could not find. Cox displayed his image at a medical meeting that evening and received enthusiastic applause.

A few days later, the x-ray image was presented in a local court where the victim was suing the man who had fired the bullet at him. The judge accepted the x-ray image -- apparently the first of millions of x-rays that have been presented to courts around the world in a century and more.

In the early months and years of x-rays, reports on their production came mostly from physicists who possessed electric current generators, vacuum tubes, and glass films, which were as sensitive to x-rays as to normal light exposures. During that same time, a few companies in the U.S. also began to offer comparable medical x-ray devices to any purchasers. One such device was offered for $15 including shipment anywhere in the country. And manufacturers, including inventor Thomas Edison, worked to make improvements over the physics unit used by Röntgen.

In some medical schools -- such as Harvard; Yale; the University of Pennsylvania; Case Western Reserve; the University of California, San Francisco; Johns Hopkins; and Cornell -- faculty adopted the idea of obtaining x-ray equipment to be installed in schools and/or their hospitals. Mostly, surgery departments took the responsibility. Dr. Maurice Richardson, a Harvard surgeon, made many speeches in which he predicted that surgeons should put x-ray devices in their offices and consult images before they undertook surgery.

In other areas, including small towns in Georgia, Texas, Ohio, Vermont, and other states, some young doctors were interested in buying x-ray devices, installing them in their offices, and figuring out how to operate them. Dozens of doctors from towns around the country spent weeks in Chicago and other places where physicists offered short courses in x-ray performance and interpretation.

In many of the same U.S. communities, even before the discovery of x-rays, some doctors had taken up electrotherapy. This treatment was based on the concept that subjecting patients to small exposures of electricity could help them recover from various illnesses. Some of the electrotherapists took their generators, added vacuum tubes and films, and began making x-rays.

In San Francisco, William Hearst's newspaper the Examiner established a laboratory in the newspaper building, and Philip Mills Jones, an electrotherapist at the University of California, went to work there. That was not the only newspaper involvement in x-ray's early days.

On January 11, 1896, six days after the first news stories about Röntgen's x-ray discovery, the New York Times sent a telegram to Harvard physicist John Trowbridge, asking him if x-rays could be performed and used effectively. That same day, Trowbridge and some colleagues put together an x-ray rig in their physics laboratory and produced an image of the hand of one of their physicists. They then responded telegraphically to the Times confirming the x-ray's effect and value.

There were two major medical x-ray efforts in Boston. Dr. Francis Williams, an internist at Harvard and Boston City Hospital, was later anointed "America's first radiologist." One of his first triumphant projects was identifying metal in the eye of a boy who had exploded a cartridge. With the x-ray image, Williams' brother, an ophthalmologist, removed the small strip of metal and saved the eye.

Also in early 1896, at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Walter Dodd, the hospital apothecary and photographer, was building an x-ray machine. When he tested his device in February, he involved several medical students in the earliest examinations.

One of them was Harvey Cushman, who was finishing his medical training at MGH and would soon move on to Johns Hopkins to begin a surgical residency. When he went to Baltimore in the spring of 1896, he took with him an x-ray tube he had purchased and began making a few x-ray images at Johns Hopkins.

To do so, he had to set up a generator, connect the x-ray tube, procure a glass film, turn on the x-ray system, develop the films, and then make his own interpretation. He dropped his x-ray efforts as he got into surgery. But the medical school authorized the acquisition of more functional x-ray devices and allowed other medical students to use them. That led Fred Baetjer, a newly graduated medical student, to take up radiology and develop the science for 30 years before he died of radiation exposure.

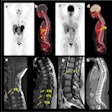

In 1901, when Francis Williams published his classic text on x-ray applications, he included a paragraph summarizing some of the productive areas.

"Measurement of the heart, aneurysms of thorax, new growths, glandular changes, diverticula of esophagus, abscess of lung liquid in plural cavity, pneumohydrothorax, pneumopyothorax, emphysema of lungs, pneumonia, spinal meningitis, pulmonary tuberculosis, can all be detected and described by x-ray studies," he wrote.

And physicists and physicians went on writing scientific articles about x-ray production and function.

Otha W. Linton, MSJ, retired in 1997 as the associate executive director of the American College of Radiology (ACR) after 35 years. He also served as executive director of Radiology Centennial in 1995. Mr. Linton holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from the University of Missouri and a Master of Science in journalism from the University of Wisconsin. His work has been published widely in the U.S. and abroad, and he is a regular contributor to several journals including Academic Radiology, the American Journal of Roentgenology, Radiology, and the Journal of the American College of Radiology. He joined the ACR staff in 1961 and had a key role in its growth. Over the years, his responsibilities with the ACR included government affairs, public relations, marketing, publishing, industrial liaison, and international relations. Just before his ACR retirement, he became the executive director of the International Society of Radiology and continues in that role. Also, since his retirement, he has written and published 14 histories of radiology societies and academic centers.

Sources

Gagliardi RA, McClennan BL. A History of the Radiological Sciences: Diagnosis. Reston, VA: Radiology Centennial Inc.; 1996.

Histories of radiology of the University of Pennsylvania; Boston University; Massachusetts General Hospital; University of California, San Francisco; Stanford University; Johns Hopkins.

Linton OW. Moreton lecture. Texas Radiological Society annual meeting; 1995.

Williams FH. The Roentgen Rays in Medicine and Surgery as an Aid in Diagnosis and as a Therapeutic Agent. New York, NY: MacMillan; 1901.