Pictures may tell a thousands words, but art can also hide deep secrets. It’s the job of French radiologist Dr. Elisabeth Ravaud to discover what lies beneath some of the world’s greatest paintings and sculptures.

Ravaud heads the radiographic facilities at the Laboratoire de Recherche des Musées de France, working in a maze of offices and laboratories hidden beneath a wing of the Louvre Musuem in Paris. Along with her colleagues, Ravaud examines dozens of paintings each year by some of the world’s most famous artists: Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Botticelli, Renoir.

Ravaud worked as a hospital radiologist for more than 10 years, but the stress of dealing with the French healthcare system left her longing for a career change. Still, she wanted to continue using her painstakingly honed imaging skills. The opportunity to combine her training in radiology and her love of art materialized in 1994. Although still licensed and qualified to work as a radiologist in France, Ravaud has never looked back.

Hospital radiologists in Europe and the U.S. occasionally image art works for special projects, or perform CT scans of mummies, but Ravaud may be the only radiologist in the world working full-time with art.

Several museums possess outdated mobile x-ray machines, but the laboratory beneath the Louvre has a unique setup of modern industrial x-ray equipment (produced by a division of GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI) in a fully shielded dedicated imaging area. The radiographic techniques used by non-imaging professionals at some museums do worry Ravaud. "I don’t think they understand enough about radiation protection," she said.

A French museum requests an x-ray of a painting or sculpture after visual examination, and other techniques -- including chemical analysis -- suggest there is more to a picture than meets the eye. For example, a Louvre expert may notice that the design does not correspond with the thickness of the paint. A painting may hide another painting underneath, sometimes by a different artist. Occasionally, a museum may ask Ravaud to image a painting being considered for purchase or for sale.

Before x-raying a work of art, Ravaud spends several hours reading the files on the piece and on the artist, and looking at photographs of the painting. She sometimes compares these to photos of other paintings, either by the same artist or from the same period.

Obtaining radiographs of the artwork can take up to half a day, depending on the size of the painting. Although most of the works that she images measure less than four square meters (43 square feet), some have been more than twenty square meters (215 square feet), which can be an obstacle.

"We can only do plain-film x-rays," Ravaud said. "It would be nice to do CT scans for some paintings or sculptures, but of course they wouldn’t fit into the CT scanner, and they could be damaged."

The real challenge is interpreting the radiographic images of the art. Ravaud can spend entire days reviewing a single image, comparing what she sees on her massive viewbox with a photo of the painting and the history of the work. Although she normally deals with paintings that have verified history (known as "provenance"), occasionally she encounters misidentifications or even forgeries. "We are always learning something new when we x-ray a painting or sculpture," Ravaud said. "It’s fascinating work."

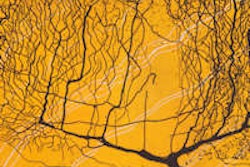

X-rays can reveal startling information about an artist’s technique. Earlier this year, Ravaud and her colleagues solved a puzzle surrounding a famous wax statue of Napoleon III on his horse. Wax sculptures tend not to survive very long because the material is fragile and extremely sensitive to temperature changes -- too much heat and it melts and loses shape; too much cold and it becomes brittle and falls apart.

Sculpted in 1870 by Alfred Jacquemart, the statue was one of a small collection at the Louvre that had retained its form and beauty. Radiographic analysis showed Jacquemart had employed an unusual method of creating the statue, which may have contributed to its survival (MedHunters Magazine, Fall 2002).

The body of the horse was modeled around a metal rod. Metal also was used at other points in the statue, including in the horse’s tail, which was molded around a large bent round-headed nail. These metallic substances appeared on the x-rays as opaque objects, whereas the wax was almost translucent. The radiographic findings led the researchers to conduct chromographic analysis on the sculpture

Ravaud’s services are in high demand from French museums, and she has had to add a sculpture specialist to the research team.

"I now deal mostly with paintings and my colleague handles objects," she explained. "He is not a radiologist, but a photographer, so we have different ways of looking at images. Our two perspectives blend well together."

Ravaud’s career has taken another turn as well. She is often called on to speak to art conservators from museums around the world, and has appeared on numerous French and Asian television documentaries on art.

"People take a keen interest in x-rays of paintings," Ravaud said. They, like Ravaud, are intrigued by the extent to which appearances can be deceiving -- in paintings as well as in people.

By Brenda TilkeAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

November 1, 2002

Related Reading

Radiography meets flower power in RT's art, July 17, 2001

Mummyography: Images reveal secrets of ancient remains, December 20, 1999

Copyright © 2002 AuntMinnie.com