In November 2005, the North Korean government urged its female citizens to abandon wearing trousers and don traditional Korean attire instead. They argued that it was important to maintain cultural traditions during a time when "(Western) imperialists are maneuvering to spread the rotten bourgeois lifestyle inside North Korea" (Boston Globe, November 4, 2005).

The communist North Korean regime's comments weren't completely off-base, although pants may not have been the most appropriate target of criticism. Certainly the "Westernization" of other countries has resulted in a wealth of political and financial opportunities. But research has shown that when it comes to physical well-being, a shift to a more Westernized lifestyle -- fattier diet, higher stress levels, less exercise -- has a detrimental effect on the health of the citizens of non-Western countries.

The trend is particularly evident in women and the incidence of breast cancer. Two recent studies, out of South Korea and Israel, took a closer look at this issue. While the Korean group assessed the current state of breast cancer occurrence in their country, an Israeli sociologist outlined a disconnect between minority women and mainstream medical institutions. In both cases, breast cancer screening, or the lack thereof, played a major part in the evolution of a disease that was once considered a Western problem.

Breast cancer in the 'land of morning calm'

In the first paper, Dr. Byung Ho Sun and colleagues from the Asan Medical Center in Seoul evaluated the clinical and epidemiologic characteristics of breast cancer in their country from 1989 to 2004.

The researchers said that they undertook this research because the incidence of breast cancer in Korea has steadily increased over that 15-year period. It has become the most common cancer diagnosed in Korean women since 2001, they pointed out, owing to the "Westernization of the lifestyle, decreasing rates of birth and breastfeeding, and increasing number of regular checkups for breast cancer" (Archives of Surgery, February 2006, Vol. 141:2, pp. 155-160).

They mined data from 5,001 breast cancer patients, the overwhelmingly majority of whom (99.4%) were women. A cancer diagnosis was most frequent in women in their 50s, and premenopausal women younger than 50 years constituted 69.9% of the patients.

"This age distribution pattern differs from that of Western countries and demonstrates that the peak age of breast cancer is 10 to 20 years younger in Korea," the group stated. "This may be due in part ... (to) relatively easier accessibility to a screening program to detect breast cancer among middle-aged women."

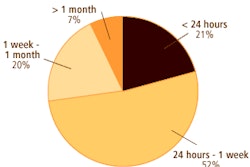

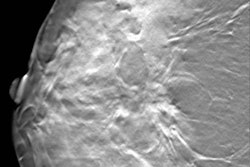

Most women (51.7%) presented with a painless breast mass. A little over 14% of the asymptomatic patients had their cancer detected through screening mammograms or ultrasound exams. This figure increased to 21% by 2003.

Applying the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification, 29.5% of the patients presented with stage I cancer followed by stage IIA in 28.5% of the cases. The proportion of stage 0 and 1 cancers increased from 34.2% in 1991 to 48.8% in 2003.

In the early part of the 15-year time period, modified radical mastectomy was the most common treatment (67.1%). Over time, that number decreased. For women who still required mastectomy, immediate reconstruction such as the transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap procedure gained popularity. On the other hand breast-conserving surgery increased, making up 39.1% of the treatment plans by 2003.

"We expect that the use of immediate breast reconstruction after mastectomy in cases of breast cancer detected at stages 0 and II by mammography will also increase because of the increased interest in the cosmetic effects of reconstructed breasts among Korean women," the authors commented.

Finally, during a median follow-up of 43 months, the five-year observed survival rate was 84.1%.

Overall, the authors noted an increase in the rate and number of breast cancer cases, an uptick in the proportion of asymptomatic screening groups, and an increase in the proportion of early breast cancer detection.

"The number of patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer increased twofold from 1996 to 2002, showing a more rapid rate of increase compared with the world average," they said. "We expect that the detection rate of early breast cancer in Korea will rise owing to increased awareness and screening mammography."

Barriers to screening

It would be a mistake to assume that women who chose not to use breast cancer screening services do so because of a lack of awareness about the disease, according to Larissa Remennick, Ph.D. But this is a common misconception that healthcare professionals have, especially when dealing with women in immigrant and minority populations.

In an article in the Breast Journal, Remennick, who is from the department of sociology and anthropology at Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan, Israel, discussed the sociocultural barriers that prevent these women from utilizing screening services. Her review was based on previous research on Russian women, as well as other minority groups (Arab/Muslim, Middle Eastern Druze), who have immigrated to Israel.

First, Remennick pointed out that "it is impossible to understand women's health decisions and actions outside of the general context of their lives." Minority and immigrant women are often considered "second-class citizens," and are expected to make complete sacrifices for their families. As a result, they may give short shrift to their own health, making preventive measures such as self-breast exam or mammographic screening the least of their concerns.

"This self-neglect does not necessarily reflect ignorance," Remennick said. "Rather, it reflects social and economic disadvantage augmented by negative emotional reaction to cancer" (Breast Journal, January-February 2006, Vol. 12: supplement 1, pp. S103-S110).

This fear of cancer is one of the psychological barriers that also stop women from complying with screening guidelines. These can range from a denial of their own susceptibility to the disease (especially if there is no family history of it) to a fatalistic view that both the illness and the treatment will only result in a mutilation of the body.

In older immigrant women (age 60 and up), a combination of fatalism and lack of social status can be the culprit. During the data collection process, Remennick said one 72-year-old Russian immigrant woman stated: "There is no point in looking for small tumors in my sagging breasts. Even if they find something and I get my breast cut off, how much time do I have left anyway? I prefer to finish my days with both breasts intact -- with or without cancer."

Remennick also described structural barriers such as a lack of health insurance or distance from the nearest screening facility. Finally, the sheer logistics of a mammogram, which requires that a woman bear her breasts to a stranger, may be enough to prevent screening compliance. "Muslim women, for example, because rules of Islam strictly prohibit nudity and self-exposure ... (may consider) the shame worse than death," she wrote.

Fortunately, there are ways for healthcare providers to overcome these obstacles, Remennick said, but it will require rethinking current approaches to screening advocacy. "No single breast cancer education and early detection program can meet the needs of all social and cultural groups," she stressed.

Remennick recommended conducting a focus group on community needs before any screening campaign is launched. Topics that need to be covered include how economically independent the women are and what gender relations are like in that community. The latter becomes particularly important in strictly patriarchal cultures in which men make all the decisions.

"Special educational programs targeting men can potentially be very effective in changing women's motivation," she said.

Educating relevant religious and cultural authors may also be value. These community experts can then assist in dispelling some of the fear that women have about breast cancer.

Access to care is another important component. A study from the mid-90s showed that, at the time, 60% of Israeli-born Jewish women, ages 50-75, complied with the recommendation for mammographic screening every two years. In comparison, only 40% of Russian immigrant women, 20% of Ethiopian women, and 20% of Israeli Arab women complied.

However, after a media campaign and the deployment of mobile mammography units in an Israeli Arab neighborhood, the compliance rate climbed to 60% by 2004 (Women's Health in Israel: A Data Book, 1999).

Finally, healthcare providers should encourage more healthcare workers with immigrant backgrounds to consider careers in breast health, Remennick said. This would open channels of communication between health professional and women in underserved communities.

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

April 14, 2006

Related Reading

Scandinavian studies take mammography to task once again, March 3, 2006

Sidestepping screening: What factors make women avoid annual mammography? October 10, 2005

Online games urge Native American women to b-i-n-go for mammograms, August 30, 2005

Bollywood-style song inspires U.K. women to get mammograms, February 10, 2004

Copyright © 2006 AuntMinnie.com