A new study in the May issue of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute indicates that women who have had false-positive screening mammograms have higher breast cancer rates later in life. But the findings were only statistically significant for women examined in the 1990s, and may no longer be relevant because of advances in imaging technology.

Researchers from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark found that women examined between 1991 and 2005 had a 67% higher rate of breast cancer later in life (JNCI, May 2012, Vol. 104:9, pp. 1-8). But the introduction of new screening technology, such as ultrasound and stereotactic breast biopsy, seemed to reduce the impact of the relationship.

Still, the authors say their study indicates that women who receive false-positive results may require closer scrutiny with subsequent screenings.

False-positives are inevitable

Screening for disease in healthy people inevitably leads to some false-positive tests in disease-free individuals, according to the researchers. So should these women simply be referred back for regular routine screening, or should they receive closer follow-up?

Lead author Dr. My von Euler-Chelpin and colleagues hypothesized that because women with false-positive tests tend to have suspicious mammographic patterns in their breast tissue (such as tumor-like masses, suspicious microcalcifications, skin thickening or retraction, recently retracted nipples, distortions, asymmetric densities, or suspicious axillary lymph nodes), these women are at a higher risk of breast cancer than women without these suspicious patterns.

The researchers used data on screening results from 1991 to 2005 culled from the Copenhagen Mammography Register; the data reflected invitation dates, participation, and test results. The team also analyzed cancer data from the Danish Cancer Registry and the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. A total of 58,003 women between the ages of 50 and 69 were included in the study.

From the time of their first screen, the women accumulated 631,039 person-years at risk of cancer. Women with negative tests contributed 580,450 person-years at risk, and women with false-positive tests contributed 50,589 person-years at risk, von Euler-Chelpin and colleagues wrote. The total number of cancers in women with negative tests was 1,969, giving an absolute cancer rate of 339 per 100,000 person-years at risk. The number for women with false-positive tests was 295, giving an absolute cancer rate of 583 per 100,000 person-years at risk.

The study found that the adjusted relative risk of breast cancer after a false-positive test was 1.67 for the entire term of the study, and that the relative risk was higher at a statistically significant level for six or more years after the false-positive test, von Euler-Chelpin and colleagues wrote.

"Earlier research has suggested that there might be an association between a false-positive test and increased risk of breast cancer, so the results were not completely unexpected," von Euler-Chelpin told AuntMinnie.com via email. "It was, however, interesting to find that the excess risk remained even 12 years after the false-positive result."

The group found that the relationship between false-positive exams and later breast cancer was higher in the group of women who underwent screening earlier in the study, a difference they attributed to the better imaging technology used later in the screening program.

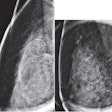

The false-positive group of women seen between 1994 and 1998 had a 65% higher risk of breast cancer (RR = 1.65, 95% CI = 1.22 to 2.24) than the group with negative tests, a difference that was statistically significant. Meanwhile, the group that received false-positive mammograms between 2001 and 2005 had a cancer rate 31% higher than those with negative mammograms, but this difference was not statistically significant.

"These important improvements coincided with major changes in screening technology, that is, the introduction of high-frequency ultrasound devices in 2001, stereotactic breast biopsy in 2002, and bidirectional mammography as standard in 2004," the team wrote.

Full-field digital mammography was not introduced in the screening program until 2006, so that technology had no impact on the results.

In any case, women should be encouraged to continue with regular screening even if they receive false-positive results, according to the researchers.

"The experience of a false-positive test causes anxiety, which may discourage women from attending screening regularly, [but] the long-term excess risk of breast cancer found in women with false-positive tests stresses the need for their adherence to regular screening," von Euler-Chelpin and colleagues concluded.

Boosts diagnostic procedures

In another study published in the same issue of JNCI, researchers found that women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) have high rates of diagnostic and invasive breast procedures after treatment with breast-conserving surgery.

Dr. Larissa Nekhlyudov of Harvard Medical School and colleagues examined data gathered from three large healthcare systems in Massachusetts and California that studied women treated with breast-conserving surgery for DCIS between 1990 and 2001, with follow-up for up to 10 years (JNCI, May 2012, Vol. 104:9).

The team calculated the percentages and cumulative incidence of diagnostic mammograms and ipsilateral invasive procedures following the initial surgical excision. They found that over a decade, 30.8% of women had diagnostic mammograms and 61.5% had ipsilateral invasive procedures following breast-conserving surgery.

"The fact that women undergoing breast-conserving surgery are likely to have diagnostic and invasive breast procedures in the conserved breast over an extended period of time is important and needs to be included in discussions about treatment options," Nekhlyudov's group concluded.