In some countries, thyroid cancer has been one of the fastest-growing diagnoses over the past 30 years. In other nations, however, malignancy rates have remained stable. What's behind the discrepancy? Researchers believe that aggressive use of imaging could be leading to overdiagnosis of thyroid disorders, according to a new analysis in BMJ.

In particular, researchers from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, believe that low-risk small papillary thyroid cancers -- the prime culprit behind this increased diagnostic incidence -- are being significantly overtreated. They are calling for a new nomenclature that removes "cancer" from the term to signify the reduced threat of these lesions ever posing a risk to patients.

Uneven growth

Small papillary thyroid cancers generate as much as 90% of thyroid cancer cases in countries that have an increased incidence of thyroid cancer. Growth in incidence has varied around the world, with the U.S. seeing a tripling of thyroid cancer over the past 30 years, while incidence has risen minimally in nations such as Sweden, Japan, and China.

Even though small papillary thyroid cancers are unlikely to cause morbidity or premature mortality in patients without a family history of thyroid cancer or radiation exposure, their diagnosis usually triggers intensive and unnecessary treatment, according to a research team led by Dr. Juan Brito of the Mayo Clinic's division of endocrinology.

"The incongruity between the increased incidence and stable mortality is most likely an effect of overdiagnosis," the researchers wrote. "This is exposing patients to treatments inconsistent with their prognosis. Both the overdiagnosis and overtreatment of this form of cancer need to be fully recognized" (BMJ, August 27, 2013).

As a result, Brito and colleagues have proposed that low-risk lesions be given a new name to convey their favorable prognosis and to help avoid overtreatment. The group defines these lesions as those smaller than 20 mm in patients with no family history of thyroid cancer or personal history of radiation exposure and no ultrasound evidence of extraglandular invasion.

Common, but rarely threatening

Papillary cancer is the most common form of thyroid cancer, contributing 85% of total detected cases. Patients with the disease have an excellent prognosis; 99% of patients with nodules smaller than 20 mm in diameter will still be alive after 20 years. Research has also shown that subclinical papillary thyroid cancers may be present in one-third of people who have died from other causes.

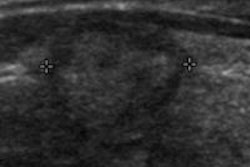

The development of neck ultrasound and ultrasound-guided biopsy in the late 1990s has allowed the detection and biopsy of nodules as small as 2 mm. Ready access to portable ultrasound machines and imaging reimbursement policies have led to the routine use of neck ultrasound scans, which have increased by 80% in general endocrinological services over the past few decades, according to the researchers.

Greater use of CT and MRI for other indications has also led to incidental detection of thyroid nodules.

"Today, more patients receive a diagnosis of thyroid cancer after an evaluation of an incidentally found thyroid nodule than after evaluation of a symptomatic or palpable nodule," the authors wrote.

Studies have demonstrated that small papillary cancers may never progress to cause symptoms or death, the researchers noted.

"The most compelling evidence that patients with low-risk cancers are being overtreated is that despite a threefold increase in incidence of papillary thyroid cancer over the past 30 years, the death rate has remained stable," the authors wrote. That rate was 0.5 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 2009, identical to the 0.5 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 1979.

Thyroidectomies have increased by 60% over the past 10 years -- and they are expensive. They also come with a risk of complications. Furthermore, the use of radioactive iodine has grown dramatically in patients with low-risk thyroid cancer, despite recommendations against its use in these cases. Radioactive iodine has both short- and long-term side effects, the researchers noted.

A new identity

To address the issue of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, the researchers suggest that low-risk lesions (defined as smaller than 20 mm in patients with no family history or radiation exposure and no ultrasound evidence of extraglandular invasion) instead be referred to as micropapillary lesions of indolent course (microPLICs) to convey their favorable prognosis.

In addition to reframing care of these patients and avoiding overtreatment, this new nomenclature might improve patient recruitment into trials evaluating active surveillance versus immediate treatment, according to the authors. Patients with low-risk lesions should also be offered the option of surveillance to detect changes suggesting progression.

"Although there is currently no evidence-based surveillance schedule, it might follow a similar path to the one used after thyroidectomy, including yearly neck ultrasonography and physical examination," the authors wrote. "Patients with lesions that are stable or shrink could then be followed up less often than those whose nodules increase in size (change in volume > 20%)."

The researchers emphasized that the overdiagnosis and overtreatment of small and indolent thyroid cancer needs to be fully recognized.

"A change in nomenclature for low-risk cancers, as we have suggested, here, could help this and make it easier to give patients the choice of active surveillance," the authors concluded.