Separating neurofibromas from schwannomas, also known as neurilemomas, is crucial as treatment may require grafting to preserve function. Even after the distinction is made between these nerve-sheath tumors, neurofibromas require additional analysis, depending on the subtype, which can again influence whether a patient must undergo complete surgical resection.

For imaging experts, the question is which modality is up to the task of making that key differential diagnosis? Unfortunately, ultrasound is not the right test, according to radiologists from Taiwan. In a recent paper, they explained how sonography falls short in making the distinction between schwannomas and neurofibromas in the extremities and superficial body.

However, musculoskeletal imaging specialists writing in the American Journal of Roentgenology had better luck with MRI and CT. They described the imaging appearance of diffuse neurofibroma in their multimodality study, and also conducted a demographic analysis to better define the population most affected by neurofibromas.

Similar soft-tissue masses

For their retrospective analysis, Dr. Hong-Jen Chiou and colleagues at Taipei Veterans General Hospital and National Yang Ming University, both in Taipei, looked at 71 patients with 76 pathologically proven lesions (50 schwannomas and 26 neurofibromas). Ultrasonography was done on one of four different units with either curved- or linear-array transducers.

Tumors were characterized based on the following:

- Size

- Shape

- Location: upper or lower extremities, superficial trunk

- Echogenic capsule

- Echogenicity compared to adjacent muscle

- Posterior acoustic shadowing or enhancement

- Cystic changes (anechoic region of greater than 0.3 cm)

- Presence of the target sign

- Relationship with adjacent nerve

In addition to standard sonographic studies, some tumors underwent color Doppler analysis with the authors looking for lesion vascularity, which was quantified on color plots. Finally, spectral analysis was done, focusing on resistive index and peak systolic velocity of the arteries within the tumors.

|

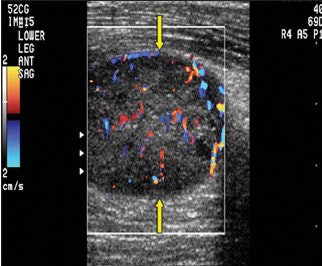

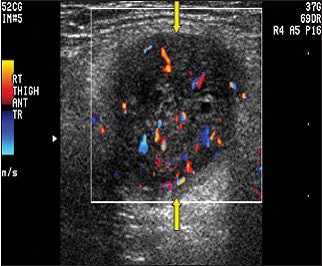

| Schwannoma in a 75-year-old man. Above, color Doppler ultrasonography of the lower anterior leg shows a well-defined oval mass (arrows) with peripheral and central color flow signals, suggesting a hypervascular tumor. Below, neurofibroma in an 84-year-old man. Color Doppler ultrasonography of the right thigh shows a well-defined mass (arrows) with peripheral and central hypervascularity. |

|

| Tsai WC, Chiou HJ, Chou YH, Wang HK, Chiou SY, Chang CY, "Differentiation Between Schwannomas and Neurofibromas in the Extremities and Superficial Body: The Role of High-Resolution and Color Doppler Ultrasonography" (J Ultrasound Med 2008:12:161-166). Images and caption courtesy of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. |

Overall, ultrasound exams did not lead to statistically significant results for making the differential diagnosis, the authors stated. The internal echogenicity was hypoechoic in 100% of the schwannomas and 100% also showed posterior acoustic enhancement. Likewise, 96.2% of the neurofibromas were hypoechoic and 96.2% showed posterior acoustic enhancement. On color Doppler, all showed hypervascular changes. Additional results are shown below.

|

These results dovetailed with the traditionally held notion that ultrasonography cannot distinguish between the two entities because both are "well-defined solid hypoechoic soft-tissue masses with posterior acoustic enhancement," the authors wrote (Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, February 2008, Vol. 27:2, pp. 161-166).

The group also found that sonography could not clearly delineate the relationship between the nerve and tumors, nor were cystic changes a reliable distinguishing characteristic. Previous reports have indicated that large schwannomas undergo degenerative changes, but Chiou and colleagues stated that they still did not find such cystic changes on ultrasound to be of value.

The authors acknowledged that the retrospective nature of this study was a limitation. They also noted one sonographic trend that may someday serve as a differential marker: Nerves entering the tumor eccentrically were generally seen only in schwannomas. Chiou has plans to conduct a prospective study to explore this particular finding, according to an e-mail interview with AuntMinnie.com.

Ultrasound has not been completely jettisoned as a diagnostic tool at Chiou's institution. Instead, it's used in conjunction with MRI, said Chiou, who is the chief of musculoskeletal radiology at the Taipei hospital.

"Eccentric association with a nerve may be better detected by MRI, if the associated nerve is large enough, due to the high soft-tissue contrast of MRI as compared to the tissue detail contrast," Chiou explained, adding that the target sign may also be better seen on MRI.

"As for small neurogenic tumors, high-resolution ultrasonography may still play an important role (because of) its better spatial resolution," Chiou said, adding that another advantage of ultrasound is its low cost and ease of use for image-guided biopsy.

Defining diffuse neurofibroma

Unlike localized or plexiform neurofibromas, not much is known about the diffuse subtype, according to Dr. Douglass Hassell and colleagues from the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, FL; the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in Washington, DC; and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, MD.

"Diffuse neurofibroma is a poorly defined lesion that spreads along connective tissue septa and surrounds rather than destroys adjacent normal structures," wrote Hassell's group. "It has been reported to occur most commonly among children and young adults, typically involving ... the head and neck.... Complete resection is often difficult because of the extensive and infiltrative nature of many of these lesions" (AJR, March 2008, Vol. 190:3, pp. 582-588).

For this retrospective review, the authors started out with 339 patients who met their inclusion criteria for diffuse neurofibroma. Available demographic data included age and gender. Of those 339, a subset of 10 had diagnostic-quality MR, CT, and ultrasound images on hand.

Among the 10 patients, eight T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and contrast-enhanced MR studies were done on which lesion signal intensity was evaluated. Five plain CT and contrast CT scans were performed and evaluated for lesion attenuation relative to skeletal muscle. Finally, one sonographic study was done with lesion echogenicity compared to nearby normal tissues.

The exams were reviewed by the radiologists for lesion size, including maximal dimension, and dominant growth pattern (plaque-like, infiltrative, mass-like, mixed).

According to the imaging-based results, the majority of diffuse neurofibromas were seen on the trunk and the head and neck. Most lesions were larger than 15 cm and a plaque-like pattern of growth dominated, with a mean plaque thickness of 2.5 cm.

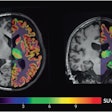

On the T1-weighted MR studies, signal intensity was similar to or mildly higher than that of skeletal muscle. On T2-weighted imaging, lesions were either mildly or markedly hyperintense to muscle. Enhancement was universally intense on contrast-enhanced MR.

|

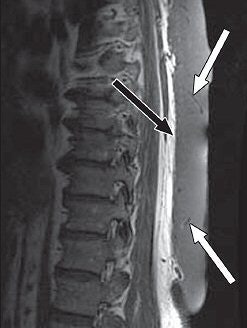

| A 65-year-old man with plaque-like diffuse neurofibroma. Above, sagittal T1-weighted MR image (TR/TE, 500/16) shows thick plaque-like diffuse neurofibroma involving skin and subcutaneous tissues of back. Deep aspect (black arrow) of mass is well-defined, and deeper subcutaneous tissues are uninvolved. Small flow voids (white arrows) reflect prominent internal vascularity. Below, sagittal T2-weighted MR image (3,200/104) shows diffuse neurofibroma (white arrows) that is markedly hyperintense in relation to muscle (black arrow). |

|

| Hassell DS, Bancroft L, Kransdorf M, Peterson JJ, Berquist TH, Murphey MD, Fanburg-Smith JC, "Imaging Appearance of Diffuse Neurofibroma" (AJR 2008; 190:582-588). |

Attenuation on unenhanced CT varied, from lower than that of skeletal muscle, similar to skeletal muscle, and similar to fat. On contrast CT, attenuation was similar to muscle. Absolute enhancement could not be determined because no patient had both types of CT studies. Finally, on ultrasound, the neurofibroma exhibited hyperechoic plaque-like involvement.

In an e-mail to AuntMinnie.com, Hassell discussed in greater detail the strengths of the various imaging modalities used in these patients and what to look for on MRI specifically.

"MR imaging was best at defining the extent of the lesion and, with its superior contrast resolution, best able to distinguish the diffuse neurofibroma from adjacent, noninvolved structures," Hassell explained. "Standard MR tumor protocols, including T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and postcontrast T1-weighted images, should be adequate for evaluation of diffuse neurofibromas.... CT and ultrasound can also be used to evaluate diffuse neurofibroma lesions and can guide biopsy."

The demographic data based on the entire 339-patient cohort yielded some particularly interesting results, Hassell told AuntMinnie.com. "Diffuse neurofibroma has previously been reported most commonly in children and young adults, involving the head and neck region most frequently. Based on our results, it is clear that diffuse neurofibroma affects a much wider age range of patients with a more even distribution of cases between the head and neck, trunk, and extremities," Hassell stated.

The mean age of the patients was 35.1 years. Trunk lesions were seen in 35% of the cases and extremity lesions were seen in 34%, compared with 8% of head and neck lesions. Lastly, skin and subcutaneous tissue involvement was typical, as was an infiltrative growth pattern.

The authors noted that the following imaging features were strongly suggestive of diffuse neurofibroma:

- Plaque-like or infiltrative pattern

- Prominent internal vascularity

- Marked enhancement

They also saw a strong link between diffuse neurofibroma and neurofibromatosis. Hassell discussed the significance of this finding.

"In the past, the incidence of neurofibromatosis in patients with diffuse neurofibroma was reported to be around 10%," Hassell stated. "The results of our study suggest a higher incidence of neurofibromatosis in patients with diffuse neurofibroma lesions. While this association requires further investigation, patients in whom a pathologic diagnosis of diffuse neurofibroma is made may require further workup for the presence of neurofibromatosis."

Ultimately, the goal of imaging in these soft-tissue tumors will be for further workup, especially if deep extension is suspected. Imaging can define the extent of the lesions, which will be important when resection is being considered, Hassell said.

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

February 22, 2008

Related Reading

Incidental findings on brain MRI common as technology advances, November 1, 2007

Case study: Baker's cyst, October 18, 2007

PocketRadiologist: Musculoskeletal: Top 100 Diagnoses, May 14, 2002

Copyright © 2008 AuntMinnie.com