Hospitals and medical imaging centers across the U.S. are keeping a watchful eye on supplies of helium -- a key ingredient in cooling MRI magnets -- as their sources have been on strict allocations for several months.

Scheduled shutdowns for seasonal maintenance this summer by suppliers, such as Exxon/Mobil and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM), which maintains the world's largest supply of helium, have contributed to the current helium shortage.

In addition, because helium is a byproduct of natural gas, its production is dependent upon the demand for natural gas and how much of that commodity is refined. The lackluster U.S. economy has stifled natural gas demand in recent years, and last winter's mild weather also reduced the need for natural gas for heating.

Ellen Joyner, MRI service product manager for Siemens Healthcare, said the company has been on restricted helium allocations for several months now, but was notified recently that its suppliers are starting to see some light at the end of the tunnel.

"We receive notification [in late August] that they are starting to release some of the allocations from 50% to 70%," she said. "We hope to be back to what I am going to call normal allocations soon."

Multiple sources

A few years ago, Siemens had only a single source for its helium, Air Products, one of the world's largest helium suppliers. Siemens recently added Linde as its second helium source.

"We saw some of the restrictions on allocations coming, so we dual-sourced our helium," Joyner said. "As an OEM supplier to our customers, it was very important for us not to have all our eggs in one basket."

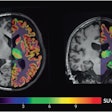

An MRI system requires helium to keep its magnet cool, especially when imaging a patient, and continues to consume helium to remain cool when the magnet is idling. An MRI system must be cooled to 4.2 K, or -452° F, and liquid helium is the most effective way to sufficiently cool the magnet to that temperature. Older magnets also "boil off" helium at a faster rate than newer magnets with more energy-efficient technology.

Typically, an MRI vendor requires a minimum threshold under which helium levels do not decrease to prevent the scanner from warming, which could adversely affect image quality. For example, Joyner said Siemens' minimum threshold is 50% to 60%. Since 2004, Siemens has designed its MRI magnets with a "zero boil off" feature, which means the magnet does not consume helium while idling.

Depending on the magnet size, an MRI system can hold between 1,500 L and 2,000 L of liquid helium. Helium suppliers generally will deliver as much as 3 dewars (1 dewar is equivalent to 250 L) to fill a magnet to 90% capacity.

Average consumption

Quantifying the average helium consumption of an MRI system is difficult, because it depends on how a facility uses its magnet, Joyner said.

"Are they using it for only five patients per day or 50 patients per day?" she said. "And what types of exams are they performing, because some are more intense than others."

Other external factors can cause additional helium consumption. For example, a facility must supply chilled water or use a chiller to keep an MRI's compressors cool and operating efficiently. If a thunderstorm were to disrupt power to the chiller, it can cause the magnet to start consuming helium to keep the magnet above its threshold temperature.

Generally speaking, the greater the magnet strength, the more helium will be consumed. For example, a 7-tesla MRI unit can consume an "enormous amount" of helium, Joyner said. "On an annual basis, a 7-tesla [magnet] can consume as much as 6,000 L [of helium]."

The price of helium is set by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management at the start of the government's fiscal year. Currently, the BLM lists the open market price at $75.75 per 1,000 cubic feet (mCf). That price will be in effect until the end of this month, which is the end of fiscal year 2012.

Traditionally, Siemens has negotiated its helium contracts on 12- to 24-month terms, but recent market fluctuations have caused its suppliers to make quarterly adjustments.

"In recent years, both of our helium suppliers have put in some clauses that allow them to increase [rates] on a quarterly basis within a specified range," Joyner said. "Sometimes, we can get a 10% to 15% increase quarter over quarter."

Helium legislation

Some relief for helium shortages may be on the way via the proposed Helium Stewardship Act of 2012 introduced in April by U.S. Sens. Jeff Bingaman (D-NM) and John Barrasso (R-WY). The bill directs the BLM to continue to sell crude helium from the country's reserve supplies to refiners beyond January 1, 2015. The act also would have BLM adopt market-based prices to help stimulate private development of helium sources, such as from natural gas exploration and production.

While a spokesperson for GE Healthcare said the company has experienced no helium shortages reported by its customers and no facilities have had difficulties in obtaining the element, Tom Rauch, global sourcing manager for servicing and aftermarket solutions at GE, in May testified before the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources in support of the proposed legislation.

At the hearing, Rauch noted that GE uses approximately 5.5 million L of helium a year at its South Carolina production facility, and allocates 6 million L annually to service its MRI systems at hospitals and other sites across the nation.

"The helium supply challenge is being managed in the installed base by filling MRIs with lesser amounts of helium per service visit," he told the committee. "This is not an ideal solution, as it means more frequent servicing, which increases equipment downtime and is ultimately less efficient in delivering care to patients."

Rauch added that GE's Global Research Centers currently are exploring the feasibility of new magnet designs that minimize the amount of helium needed as the U.S. looks to a near future where the demand for helium could fast outpace supply.