AuntMinnie.com is pleased to present Part III of a four-part white paper on pediatric imaging tips and techniques by Douglas Clark, R.T. (R) (CT).

Let's talk about the use of a newer technology in the medical imaging of pediatric patients. Although CT has been available for a few decades, over the past six years or so the advent of faster scanners and more detailed imaging have made it a better option. Multidetector scanners and subsecond acquisition are commonly available in most hospitals and some clinics, and because of that availability, the use (and sometimes abuse) of CT scanning in children has become more prevalent.

Other advantages of the newer scanners include thinner collimation, 3-7 mm depending on age, and variable pitch of 1-2 or higher. Keep in mind that as pitch gets higher, the scanner gets faster and the coverage area is extended, but inversely, your resolution decreases as pitch is increased.

The technologist should take special care to ensure that appropriate studies are being ordered. Talk to your radiologist if something seems unnecessary and let him speak with the referring physician.

Again on the part of the technologist, if you do scan the patient, be aware of your scan parameters. The type of scan (axial versus helical), collimation, pitch, mAs, kVp, and algorithm are all factors to consider. Also consider the scan delay, timing, use of contrast media, and what the physician is looking for with the exam.

CT scanning in the pediatric population presents a unique set of potential problems. Rapid respiratory rate, voluntary motion, and less body fat (you remember those days) all present unique challenges.

With regard to respiratory rate and voluntary motion, is some type of sedation appropriate for the patient? Remember that it does no good in terms of radiation dosage, patient throughput, and tech/nurse/parent frustration to repeatedly scan a child while hoping for a motionless image.

Although it is not in the tech’s job description or responsibility to physically sedate the child, because it’s happening in our "house," we need to be aware of the considerations involved in pediatric sedation.

A visit from the sandman

As much as we’d like to sometimes, it is not appropriate to sedate all of our patients. With the exception of certain procedures or patients in the ED, very seldom is sedation necessary for diagnostic radiographic procedures -- but other modalities are a different story.

CT, MRI, nuclear medicine, and other short-term, diagnostic, or surgical procedures sometimes will benefit from some form of sedation. We will discuss sedation itself and what takes place, but it’s imperative to understand that the technologist is present to scan or image the patient; at no time is it the technologist's responsibility to give sedation to or to take part in the direct sedation of the patient. There have been both deaths and lawsuits attributed to technologist participation.

The sedation itself is necessary to:

- Reduce extraneous motion and ensure a proper exam.

- Minimize physical discomfort and negative psychological and physiological responses to treatment by providing analgesia, behavior control, and the potential for amnesia.

The next consideration is for the radiologist or nurse to decide what type of sedation is appropriate. There are three main categories, but only one that is typically seen in radiology.

- Light sedation -- for example, Xanax or an equivalent. This is usually administered to adults to combat anxiety or claustrophobia. Allows to patient to rest or sleep.

- Conscious sedation -- a medically controlled state of consciousness that allows the patient to maintain a patent airway independently.

- Deep sedation -- a chemically induced state that may be associated with a partial or complete loss of airway. Patients are usually intubated in these cases.

Administration and equipment

Guidelines established by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) and the American Academy of Pediatrics state that only a registered nurse or a physician may administer sedation to a patient. While a patient is being sedated, there must be two people in the department who are Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) certified.

Some of the necessary equipment present should be:

- A pediatric crash cart with appropriate drug boxes and airway kits -- you do not want to be scrambling around, in the event of a problem, trying to find the appropriate equipment.

- The patient must be on a pulse oximeter (PaCO2 monitor) for the entire time he or she is sedated. This is a big must. Children’s heart rates are so rapid and their respirations can be so shallow when sedated that it is sometimes impossible to tell if they’re moving enough oxygen. The pulse ox will tell the nurse if the level of oxygen in the patient’s blood (generally 97%-100%) is appropriate.

- The nurse must have the patient’s weight to calculate drug dosage and a good history and physical (H&P) on the patient.

The day before the procedure, the nurse usually will call the parents and ask that they deprive the child of sleep the night before. This is usually tougher on the parents than it is on the child, but it ensures that:

- The child will go down easier, sometimes without sedation for certain procedures such as a sinus CT

- If we do have to sedate the child, it typically requires far less sedation to achieve the desired effect.

The child also needs to be NPO (nothing by mouth) for at least 4-6 hours before the procedure. This ensures that if the child’s gag reflex is stimulated for whatever reason, the child will not aspirate the vomitus.

Drugs

Two of the more common sedative agents that have been used at places I’ve scanned at (and therefore have firsthand experience with) are chloral hydrate and Nembutal. Once again, we as technologists are not required to know the pharmacological information; however, it is good practice to know what’s going on in your room and to understand it.

Chloral hydrate is a sedative used for younger children under 25 lbs. For some reason, in our experience, in children over 25 lbs the chloral actually reversed and the patient became more active and animated. Chloral is available in both oral and rectal suppository forms, but the oral stuff tastes really nasty.

The problem with that is that if the child spits out the medication (I tasted it and I would) you’re not sure how much got ingested and how much came out. It was the practice of the team I worked with to order rectal chloral hydrate, eliminating the taste issue and knowing exactly how much of the drug was delivered. Chloral hydrate takes about 20-30 minutes to kick in (so don’t even try to put the patient on your table before that) and usually lasts anywhere from 60-90 minutes.

Nembutal is an intravenous (IV) medication that works well on patients regardless of their age or weight. It’s amusing to watch the faces on tired parents as we start the child’s IV. Initially, they’re screaming and kicking (the child, not the parent), but as soon as the Nembutal goes in, they’re out.

Nembutal kicks in almost immediately, and the child stays out for anywhere from 1-4 hours depending on the dosage. Our team preferred to give half of whatever the patient's body weight allowed and titrated the rest as necessary. By using the least amount of medication, the child recovered more quickly and the parents were pleased.

During the sedation, the RN would monitor and document all readings and patient status, and the patient would be recovered in the radiology area until they woke up. They must be easily arousable, able to maintain their own airway, and be well hydrated.

One other major point to mention about sedation with these particular drugs is if the patient has an allergic reaction to the sedative, there is no reversal agent. Therefore emergency equipment must be close at hand and trained personnel must be available.

A reaction to the chloral hydrate simply causes the child to become much more active and animated. It is inappropriate to try another drug until this wears off, so you’re left with either a waiting game or rescheduling of the procedure.

The Nembutal is a bit more serious. Patients having a paradoxical reaction to this sedative almost immediately begin to react with a tonic-clonic contraction and relaxation of the muscles.

They become very strong. I actually had a seven-year-old girl (about 60 pounds or so) have a paradoxical reaction before a CT of her sinuses. I was trying to hold her on the table so the radiologist and nurse could do their thing, and she was actually lifting me off of the floor -- not an easy feat considering that I weigh more than 200 pounds.

In this type of reaction, the patient’s airway must be monitored carefully and the pulse ox can drop unexpectedly. In the previous case, the child’s pulse ox dropped recurrently into the lower 90s and she was transferred to the pediatric ICU for 24-hour observation. She was discharged the next day with no memory or aftereffects of the events, along with parental instructions that she was never to receive Nembutal in the future.

How else might the issue of pediatric sedation become a problem for the technologist? How about your patient from the floor who’s been sedated for a CT of the temporal bones and is brought down by the nurse (who leaves because she has three more patients to care for) and who is not on a pulse oximeter? If something happens to that patient, directly or indirectly, while in your care, you can be held responsible. It’s important to be aware of the ramifications.

How about a young child as an outpatient for an MR procedure? The radiologist has decided that chloral hydrate is appropriate and instructs the MR tech (because they don’t have a nurse at the facility today) to administer ‘x’ amount of chloral. When the child does not go out, the radiologist orders another dose, which the tech measures out and gives to the patient. The patient is placed in the magnet and on completion of the exam, they realize the child is not breathing, and hasn’t been for a while. Sounds like something none of us would do, but it has happened.

The topic of pediatric sedation for imaging procedures is one that should be addressed on many levels before being instituted. When the radiologists, nursing staff, EDs, and technologists are trained appropriately and aware of the potential problems, sedation can really be an easier, more time-efficient adjunct to certain imaging procedures. It ensures a decrease in procedure time, radiation dose (in the form of repeats due to motion artifacts), and the potential for a more definitive diagnosis.

Contrast

I mentioned earlier the lack of intraperitoneal body fat in children; this is where your oral (GI) and/or IV contrast media play a part.

IV contrast media (nonionic) is necessary for both vascular and tissue opacification, but remember that the volume, delivery method, and scan delays are very different from those of adults.

Contrast volume is typically 1-2 cc/kg of body weight, depending on your institution’s policies.

Delivery of IV contrast is typically performed via a hand-injected bolus through a peripheral IV site. A 22-gauge IV is preferred for ease of use, but a 24 gauge is sufficient. Auto-injectors are typically not used in children as they may increase the risk of extravasation.

Scan delays can be achieved a couple of ways: calculation using SmartPrep (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI), CareBolus (Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA), or another bolus-timing software program. Alternatively, you can use an empiric delay, which is the present choice of my institution and of others with whom I have spoken with recently.

Usually we use a 15-second delay, after completion of the injection, for a chest CT and 20-second delay, after completion of injection, for an abdomen CT. This seems, clinically, to give us good soft-tissue enhancement overall.

I venture to say that most everyone uses nonionic (versus ionic) contrast media now, but there is another type of nonionic agent that we have found to be well suited to the pediatric population -- a nonionic iso-osmolar contrast agent called Visipaque (Amersham Health, Buckinghamshire, U.K.).

Visipaque causes fewer fluid shifts, less-rapid dilution, and less heat to the patient resulting from a rapid injection. In simple terms, Visipaque (being iso-osmolar) is the same osmolality as blood; therefore it has a higher viscosity than its nonionic brethren, resulting in a slower flow and a tighter bolus. It also has a very low renal toxicity, and being safer on the kidneys makes it ideal for the pediatric population.

|

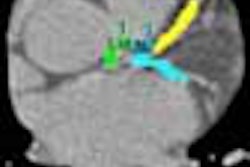

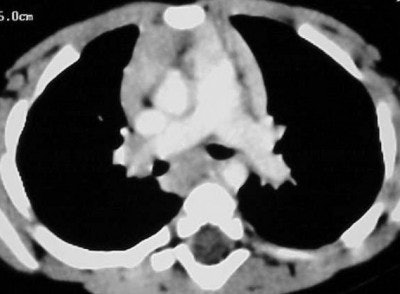

| Figure CT 1 |

|

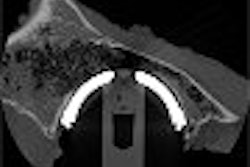

| Figure CT 2 |

Figures CT 1 and CT 2 are 8 cc of Visipaque hand-injected into a 12-year-old girl through a 22-gauge IV with a 15-second delay. Figure 1 shows good opacification of the pulmonary arteries while figure 2 shows the abdominal aorta clearly and the spleen and liver in the arterial phases.

I found this contrast by trial and error and it has proven itself unequivocally in my imaging. The only downside to Visipaque is the cost, almost two times the price of nonionic media. Therefore, use on a case-by-case basis, for example, in pediatrics or CT angiography.

GI contrast is another helpful area in pediatric imaging. Due to the lack of intraperitoneal fat in children, differentiation of bowel from abscess or tumor can be quite difficult for radiologists. A good oral prep can help to solve that problem.

Typically either dilute barium, such as EZ-Cat (E-Z-EM, Lake Success, NY), or a water-soluble, iodine-based media, such as MD Gastroview (Mallinckrodt, a business unit of Tyco Healthcare, Hazelwood, MO) is used depending on the radiologist's preference.

Shown below is the guideline we use for administration of GI contrast, about 60 minutes prior to scanning time.

|

0-1 year |

2 oz. |

|

1-2 years |

4 oz. |

|

2-4 years |

6 oz. |

|

5-8 years |

10 oz. |

|

8-10 years |

12 oz. |

|

10 years |

Adult dosage |

Use your judgment: if the patient is an eight-year-old weighing in at 140 lb or so, use an adult dose.

We do not use oral contrast in settings of acute trauma, and it is contraindicated in patients without a gag reflex or intubated patients with an uncuffed ET tube.

Join us on May 12 for Part IV: Imaging the pediatric patient: CT applications

By Douglas Clark

AuntMinnnie.com contributing writer

May 7, 2004

Clark is a staff CT technologist with University Health System in San Antonio, TX, and has been a radiographic technologist since 1990.

Bibliography

Costello P, Dupuy, DE, Decker CP, Tellor "Spiral CT of the Thorax with Reduced Volume of Contrast Material," Radiology 1992; 183; 663-666

Gulcziewski Victoria RN, Carvajal Hugo MD, "Procedural Sedation Guidelines Summary" 2003

Nycomed-Amersham, "Visipaque," March 2001

Related Reading

Part II: Imaging the pediatric patient: Diagnostic radiography, April 26, 2004

Part I: Imaging the pediatric patient: Beyond the smiles and stickers, April 22, 2004

Misread scans often lead to osteoporosis diagnosis in children, March 22, 2004

PET/CT brings added value to pediatric oncology, February 27, 2004

Ultrasound, CT, or MRI best for pediatric foot toothpick puncture injuries, Feberuary 25, 2004

Copyright © 2004 Douglas Clark