Since the discovery of x-rays in 1896, scientists across a broad range of disciplines have acknowledged medical imaging as a useful tool to probe more deeply -- and noninvasively -- the mysteries of the world around us. Radiologists and archaeologists have long been working together to uncover information about ancient artifacts without disturbing them. Although conventional x-ray has produced invaluable information, CT technology, particularly spiral CT with multiplanar display capabilities, is proving helpful for archaeological research.

The Soap Lady comes clean

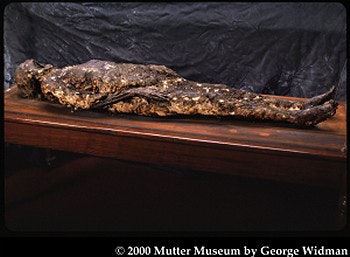

Last year, the Mutter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia asked the Imaging Science and Information Systems Center (ISIS) at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, to image the museum’s "Soap Lady Mummy" using a portable CT unit.

|

| A CT scanner was moved into the main ballroom of the Mutter Museum; the exam had to be done over the course of six hours in order to minimize heat exposure. Image courtesy of the Mutter Museum, College of Physicians of Philadelphia. |

Radiologic technologist David Lindisch used a Tomoscan-M (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA) to image the body of a 40-year-old woman who had been buried in a Philadelphia cemetery in the 1830s or 1840s. Lindisch's team shared their results in a poster presentation at the 2002 RSNA meeting in Chicago.

Due to the high alkaline content of the cemetery soil where the woman was buried, the fat tissues of her body turned into a waxy, soap-like substance, called adipocere, through a process called saponification.

Although the Soap Lady had been imaged in 1987 with conventional x-ray, the CT exam found new information, including a 7-mm ureteral stone, an 8-mm gallstone, a calcified aorta and calcified arteries in the brain, and brain atrophy. Because of the limitations of the heat units of the x-ray tube, the exam was done in three stages over six hours, with 2-mm slices and 1-mm reconstructions.

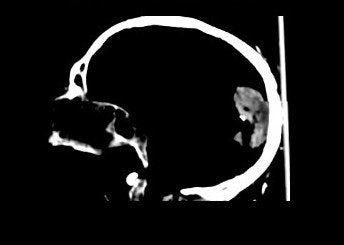

|

A lateral skull radiograph (above) and a lateral CT scan (below) of the Soap Lady. The CT scan parameters included 2-mm collimation with 1-mm slices for optimal 3-D reconstruction. The CT scan shows the calcified arteries in the brain. Images courtesy of David Lindisch and the department of radiology, ISIS Center, Georgetown University Medical Center.

|

"Researchers did regular x-rays on this mummy, but until we performed the CT exam, they had no idea that the woman’s organs were still semi-intact," Lindisch said.

The Iceman cometh

When the so-called Iceman mummy was discovered in the Tyrolean Alps in 1991, archaeologists couldn’t believe their luck. A brief warming trend exposed the 5,300-year-old body just long enough for a German couple on a hike to discover it. The mummy was then transferred from its icy bier to the University of Innsbruck’s department of anatomy in Austria, where an international cohort of researchers began to examine it. They used medical imaging technology to gather the most anatomic information possible with the least damage to the body.

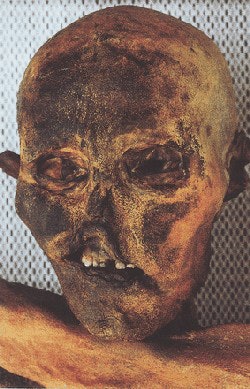

|

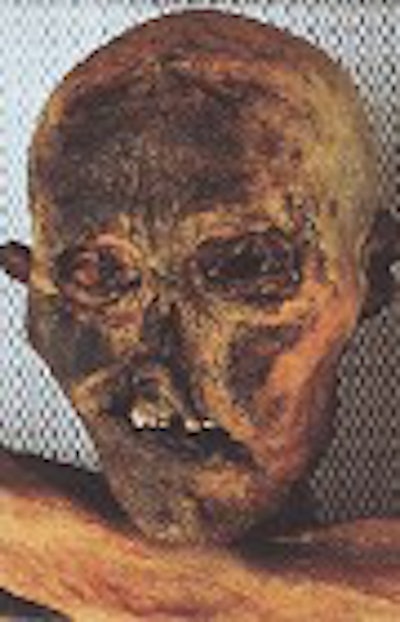

| This frontal photo of the Iceman was taken in September 1991 and shows dry contracted skin resulting from the natural mummification process. The eyeballs are completely collapsed due to dehydration; the upper lip is deformed; and the nose is flattened, most likely because of the prone position of the corpse as it bore the weight of ice and snow. Murphy WA Jr., zur Nedden D, Gostner P, Knapp P, Recheis W, Seidler H. "The Iceman: discovery and imaging," (Radiology 2003, Vol. 226, pp. 614-629). |

Conventional CT and radiography were used as soon as the body was discovered; portable CR was used about a year-and-a-half later, according to Dr. William Murphy, Jr., and colleagues (Radiology, March 2003, Vol. 226:3, pp. 614-629).

Spiral CT scans were conducted two-and-a-half years after the man was found, and a third collection of spiral CT images was made 10 years after the initial one. MRI and ultrasound were not used, since the body was devoid of fat and dehydrated.

|

| This radiograph, taken in May 1993, shows variable shrinkage of the brain. The body was in a supine position. The frontal view of the head shows the shrunken brain surrounded by dura mater (arrows) that did not shrink as much as the brain did. The arrowheads point out the falx cerebri within the interhemispheric fissure. The brain exhibits variable opacity, probably due to variation in the physical and chemical alterations that accompanied an intermittent or inhomogeneous mummification process. Murphy WA Jr., zur Nedden D, Gostner P, Knapp P, Recheis W, Seidler H. "The Iceman: discovery and imaging," (Radiology 2003, Vol. 226, pp. 614-629). |

With time and technology improvements, scientists gathered new information about the Iceman and his life, Murphy told AuntMinnie.com via e-mail. Each generation of medical imaging technology yielded better images, and the radiologists and other scientists working with the Iceman studied the images in several iterations.

For the first time, according to Murphy, CT data were used in a technique called stereolithography to produce a true plastic replica of the Iceman’s skull, allowing researchers to leave the mummy’s actual skull intact. Medical imaging helped researchers clarify the Iceman’s manner of death -- bleeding from a vascular injury -- and provided an anatomic "roadmap" for later research.

"The images displayed discrete and accurate anatomic information regarding the location and condition of internal organs," Murphy wrote. "Based on the information derived from the images, scientists could determine whether or not biopsies could be performed, what biopsy method might be best in each circumstance, and what approach to biopsy would be most effective."

Spiral CT unwraps Egyptian burial practices

In 2001, Dr. Frederico Cesarani and colleagues from the University of Torino, Italy, examined 13 Egyptian mummies (10 adults and three children) in an effort to evaluate the effectiveness of multidetector CT and 3-D reconstructions for studying mummies noninvasively.

|

| The Mummy of Harwa, Valley of Queens, is housed in the Egyptian Museum in Torino, Italy. It dates from Dynasty XXII to Dynasty XXIII. Cesarani F, Martina MC, Ferraris A, Grilletto R, Boano R, Marochetti EF, Donadoni AM and Gandini G. "Whole-Body Three-Dimensional Multidetector CT of 13 Egyptian Human Mummies," (AJR 2003, Vol. 180, pp. 597-606). |

The bodies dated from Dynasty III to Dynasty IV (2650 to 2450 BC) and from the Ptolemaic period (332 to 330 BC) to the Roman period (30 BC to 395 AD). The mummies’ external wrappings were in good to excellent condition, and had already been imaged with conventional x-rays.

CT has been used to study Egyptian mummies since 1977, but few whole-body explorations with 3-D reconstruction have been performed, according to the researchers (American Journal of Roentgenology, March 2003, Vol. 180:3, pp. 597-606).

Cesarani and his fellow researchers used a LightSpeed QX/i, a multidetector CT unit (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI) that performed single volumetric acquisitions of the whole body, including the lower extremities. They assessed the sex and age of each mummy; the embalming techniques used with each; and conditions of each mummy’s skeleton and soft tissue.

They reported that a slice thickness of 2.5 mm with a reconstruction interval of 1.25 mm were the best parameters to gather accurate multiplanar and 3-D reconstructions.

They also performed 3-D reconstructions, which helped them discover how the mummies might have looked in life, and shed light on the skill levels of the embalmers and the particular embalming techniques used. Egyptians dehydrated bodies with natron -- a compound of sodium salt, potassium, magnesium, and aluminum -- or with cedar oil; they also dehydrated the bodies with natron and then eviscerated them, preparing the organs separately for burial.

|

| Male mummy of unknown provenance, dating from New Kingdom to Third Intermediate period. Midline sagittal reconstruction of CT image with anthropometric measurements of skull marked shows basion-bregma height (129.6 mm) (arrowhead); nasion-basion diameter (96.8 mm) (small single arrow); basion-prostion diameter (96.3 mm) (small double arrows); and basion-gnathion diameter (106.9 mm) (large arrow). Cesarani F, Martina MC, Ferraris A, Grilletto R, Boano R, Marochetti EF, Donadoni AM and Gandini G. "Whole-Body Three-Dimensional Multidetector CT of 13 Egyptian Human Mummies," (AJR 2003, Vol. 180, pp. 597-606). |

The Italian group analyzed different embalming techniques by identifying the presence of objects such as stucco plaster-soaked linen wrappings and resins, wax, metal, wood, mud, or sawdust.

In their conclusion, the researchers declared that, in particular, multidimensional CT "is a fundamental tool for the study of mummified bodies. "Radiology represents an accurate, noninvasive method of evaluation, and its application has been used since the introduction of x-rays," they wrote.

"CT, in particular helical CT, followed by multiplanar and three-dimensional reconstructions, has improved both the quality and the quantity of available information of specimens not directly visible under the wrappings. The use of CT is increasingly important, especially among anthropologists and paleopathologists."

By Kate Madden YeeAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

April 23, 2003

Related Reading

Radiologist at Louvre trades healthcare for high art, November 1, 2002

CT reveals secrets of antique books and collectibles, November 28, 2001

Radiography meets flower power in RT's art, July 17, 2001

Mummyography: Images reveal secrets of ancient remains, December 20, 1999

Copyright © 2003 AuntMinnie.com