"Thank God I have this ugly fat body for which to focus on and hate and spend all my time trying to fix, change, lessen. Thank God for exercise machines, and diet pills. Thank God for weight loss. Thank God I can try and fix the outside because I just know that the inside is beyond repair."

The "inspirational" quote above was taken from a pro-anorexia (or pro-ana) Web site, one of many Internet hubs espousing the philosophy that having an eating disorder is a lifestyle, not a disease.

Whatever positive spin these women -- and 90% of those in the U.S. contending with eating disorders are young females -- might choose to put on their problems, there is no denying that their lifestyle wreaks havoc on body and mind. The long-term physical affects of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa include osteoporosis, severe dehydration, loss of menses, and the risk of heart failure. Emotionally, these patients may have to contend with a lifetime of low self-esteem, depression, panic attacks, and anxiety.

Even after their bodies have healed through intervention, the psychological trauma can persist. A recent study showed that anorexic women who have undergone treatment for three months, gained weight, and reduced psychological symptoms still continued to restrict their food intake. The former anorexic patients in the study reported that they found the situation difficult to deal with because they were given an unknown food item and were not told how many calories it contained (American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, August 2005, Vol. 82:2, pp. 296-301).

Of course, much has been made of society's role in goading women into starvation, whether it's a desire to mimic the super-skinny look of popular actresses and models, or a desire to exert some control in an increasingly chaotic world.

Rather than looking outwardly for reasons behind eating disorders, imaging specialists are turning inward to assess potential neurobiological causes for these diseases. Specifically, they are using PET to learn more about disturbances in the brain function and chemistry of women with anorexia or bulimia. A better understanding of the imbalances in the neurotransmitter systems of the brain will give clinicians better tools for fighting a disease that has the highest death rate among all psychiatric disorders.

"These are brand new technologies (in eating disorders), and I'm highly encouraged by the data," said Dr. Walter Kaye, who serves on the board of directors of the Seattle-based National Eating Disorders Association. "Imaging has a very bright future in terms of helping us understand treatment response and maybe even starting to tailor treatments for people."

Animal anorexia

A group from New York used microPET in an animal model to investigate the long-term affects of chronic food starvation on neurochemistry, as well as behavioral symptomology.

"We tested the hypothesis that chronic food restriction in the rat would decrease relative to (18-FDG) uptake, in effect modeling the cerebral glucose hypometabolism reported in the clinical population of anorexia nervosa," wrote Nicole Barbarich-Marsteller, a doctoral candidate in neuroscience at the State University of New York at Stony Brook (SUNY). "The major benefit of assessing FDG uptake in animals is that uptake occurs during the awake state, while the animal is conscious and freely moving" (Synapse, August 2005, Vol. 57:2, pp. 85-90).

Barbarich-Marsteller's co-authors are from SUNY's graduate program in molecular and cellular pharmacology, as well as from Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, NY, and New York University in New York City.

For this three-week study, nine adolescent female rats were used. During phase I, their daily food intake and weight were recorded, and they underwent a baseline PET scan. In phase II, they were divided into a control group and a food-restricted group. The latter received 40% of their baseline daily food intake until a 30% weight loss had occurred.

MicroPET imaging (R4, Concord Microsystems/CTI Molecular Imaging, Knoxville, TN) was performed after an injection of about 1.0 mCi of FDG. All microPET images were coregistered to a rat brain atlas.

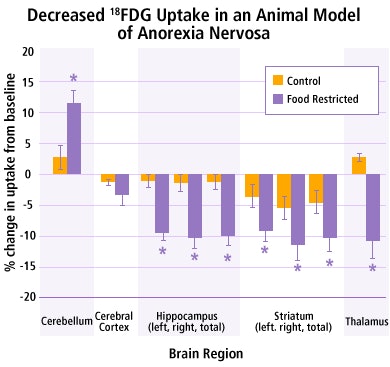

The results showed that after 24 hours of acute food restriction there were significant differences between the control group and the food-restricted group in relative FDG uptake in the cerebellum, hippocampus, and striatum. During phase II, the thalamus showed a significant increase in relative FDG uptake (see graph of results below).

|

| Graphic courtesy of Nicole Barbarich-Marsteller. |

Barbarich-Marsteller explained the long-term results in an e-mail to AuntMinnie.com. "When compared to the baseline scan, FDG uptake increased in the cerebellum and decreased in the hippocampus, striatum, and thalamus following three weeks of food restriction (compared to the control group that did not have a significant change following three weeks of free access to food)," she wrote.

An advantage of using microPET, rather than autoradiography, is that the baseline and follow-up scans can be compared in the same animal. For her current research, Barbarich-Marsteller is measuring the effects of chronic food restriction on specific neurotransmitter systems.

"I am using a different compound (11C-raclopride) to look at changes in the dopamine system (particularly at the D2 receptor), a neurotransmitter associated with reward," she stated. "Ultimately, the goal of this research is to understand the changes that occur following chronic food restriction and to develop specific pharmacological treatments that target these changes."

The behavior of bulimia

In the reward center of the brain, bulimics have much in common with other addicts. Opiate blockers, which are often given to drug and alcohol abusers, have been somewhat successful in treating bulimics. But a deeper understanding of the role of the opioid system in eating disorders is still needed.

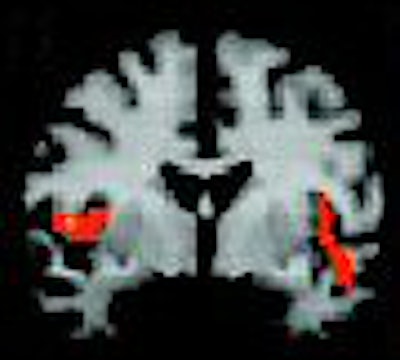

To that end, Dr. Badreddine Bencherif and colleagues compared in vivo opioid function in bulimic subjects to controls. They also correlated mu-opioid receptor (mu-OR) binding with abnormal eating behavior. They presented a parallel study at the 2005 Society of Nuclear Medicine (SNM) meeting in Toronto.

"Establishing whether the differences in mu-OR binding are reversed by successful treatment of bulimia nervosa should be a first step in helping to clarify whether these alterations are state-related or trait-related," wrote radiologist Bencherif, who is from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore. Co-authors are from the university's departments of psychiatry and neuroscience (Journal of Nuclear Medicine, August 2005, Vol. 48:8, pp. 1349-1351).

The study population consisted of eight female bulimia patients and eight healthy female controls. Both groups were instructed not to eat three hours before their PET exam. T1-weighted MR images were acquired on a 1.5-tesla scanner (Signa Advantage, GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, U.K.). PET scans (3096 Plus PET, GE Healthcare) were performed after the administration of 621.6 MBq of 11C-carfentanil.

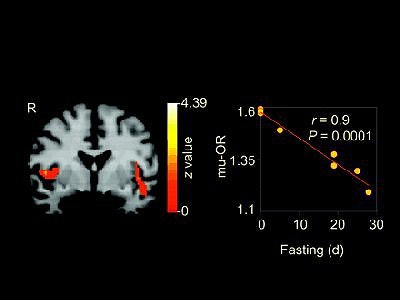

|

| Negative correlation between mu-OR binding and fasting behavior in bulimia subjects. Clusters were found bilaterally in temporoinsular cortex. Plot of fasting frequency in prior 28 days against average mu-OR binding for 44 voxels (p = 0.042; zmax = 3.68) in left temporoinsular cortex cluster reveals inverse linear relationship. Badreddine Bencherif, Angela S. Guarda, Carlo Colantuoni, Hayden T. Ravert, Robert F. Dannals, and J. James Frost. Regional mu-opioid Receptor Binding in Insular Cortex Is Decreased in Bulimia Nervosa and Correlates Inversely with Fasting Behavior. J Nucl Med 2005; 46;1349-1351, Figure 2. |

According to the results, the frequency of fasting in the prior month showed a significant statistical relationship with mu-OR binding in the temporoinsular cortex. Bulimic individuals had significantly decreased mu-OR binding in the left insular cortex. Also, lateral asymmetry was noted in the insular region, which is the primary taste cortex associated with the anticipation and reward of eating. The group concluded that changes in mu-OR binding may play a major role in why bulimics persist in such a harmful activity.

Postrecovery anxiety

In-hospital treatment programs can put anorexic patients back on track, but as many as 70% of these patients are susceptible for relapse upon entering the real world. One factor that may influence whether an anorexic will fall off the recovery wagon is the specific type of disorder, and how it relates to alterations in brain serotonin receptor binding.

In a recent study, Dr. Ursula Bailer and colleagues described the two subtypes of anorexia nervosa (AN). Restricting type anorexia nervosa (RAN) refers to those who keep a tight rein on their eating habits versus bulimics (BAN), who alternate restrictive eating with binge/purge eating.

In either case, "anorexia nervosa subtypes are thought to share some common etiological factor because they ... have many symptoms in common," wrote Bailer's group. "Several lines of evidence support the possibility that altered central nervous system serotonin (5-HT) activity contributes to the appetitive alterations found in AN" (Archives of General Psychiatry, September 6, 2005, Vol. 62:9, pp. 1032-1041).

Bailer and many co-authors, including Kaye, are from the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. Other contributors are from institutions in Vienna, Austria; Bethesda, MD; and San Diego.

For their research, the researchers paired PET with the radioligand [carbonyl-11C]WAY-100635 to assess pre- and postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptor function. The study participants had been in recovery from AN for a year or more -- 12 women had recovered from BAN and 13 from RAN. They were matched with 18 healthy controls. A measure of ketone body metabolism determined that none of the subjects were in state of physiologic starvation. MR and PET scans were obtained and co-registered; PET imaging was done after an injection of 499.5 MBq of [11C]WAY-100635.

The authors reported that women recovering from BAN had a significantly increased radioligand binding potential in the following regions of the brain compared to the control group:

- Cingulate

- Lateral and mesial temporal

- Lateral and medial orbital frontal

- Parietal

- Prefrontal cortical

In addition, higher cerebellar distribution volume of the radioligand was found for BAN patients. For women recovering from RAN, the postsynaptic receptor binding in mesial temporal and subgenual cingulated regions was positively correlated with harm avoidance. These alterations in the 5-HT receptors of RAN women may manifest as anxiety and mood disorders long before the eating disorders develop, the authors suggested.

"The data ... can be interpreted to suggest that a dysregulation of 5-HT neuronal pathways persists after recovery from an eating disorder," they concluded. "A disturbance of 5-HT neuronal function and behavioral symptoms persist after normalization of weight and nutritional status in AN."

Kaye told AuntMinnie.com that one potential use of this research is in preventing relapse in eating disorders patients.

"Various kinds of drugs, the SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) as well as some of the other drugs that we use, directly affect the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor. For SSRIs to be effective, they have to influence and down-regulate the 5-HT1A receptor," he said. "There haven't been that many studies looking at the 5-HT1A receptor and the effect of medication in humans. It's completely reasonable ... that we may able to start to understand who responds to medication or what medication."

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

September 15, 2005

Related Reading

Body fat distribution abnormal in recovered anorexics, June 22, 2005

PET shows therapy can alter opioid receptors in bulimics, June 20, 2005

Telling anorexics about bone harm may spur change, May 30, 2005

Copyright © 2005 AuntMinnie.com