There is no vulnerable plaque, only the vulnerable patient. Besides, most plaque is extraluminal, though just as deadly, and therefore all but invisible to lumen-based imaging methods. As a result, the vulnerability of patients rests more on the likelihood of plaque rupture than on the risk of occlusive vascular disease.

For these reasons and more, Dr. Steven Nissen's recent talk on the role of systemic inflammation in atherosclerotic disease bears noting.

At the 2006 Integrated Imaging in Clinical Cardiovascular Practice meeting in San Francisco, Nissen bashed the "vulnerable plaque hype-othesis" in favor of broader measures of atherosclerotic disease that recent evidence has highlighted.

"We have people with dozens of techniques out there trying to find the vulnerable plaques for prophylactic stenting and intervention. And I don't buy it," said Nissen, who is chair of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Ohio, and president of the Washington, DC-based American College of Cardiology (ACC). "It's clear that plaque rupture is the most important phenomenon in cardiovascular medicine. This process is what kills half the population in Western countries."

Despite the medical community's lopsided emphasis on stenosis detection and management, the role of stenosis in atherosclerosis is small, he said.

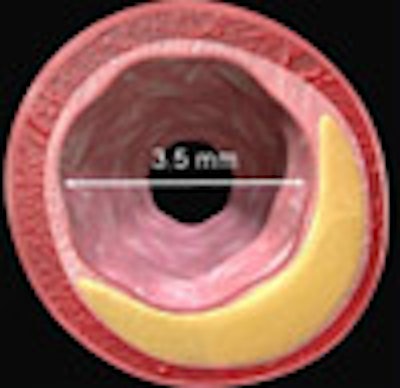

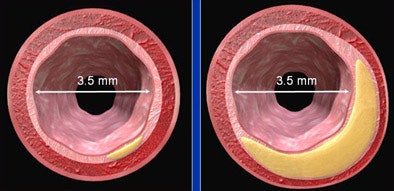

"We've learned over the last 15 years that during the development of atherosclerosis, in most patients most of the time, the lumen is not compromised," Nissen said. "That's one of the reasons why many of us have concerns about tests like CT angiography. Because only about 1% of all the plaque in the coronary arteries is actually intraluminal. Most of the plaque is extraluminal."

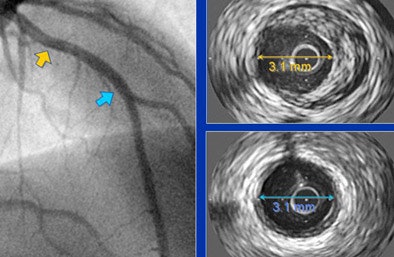

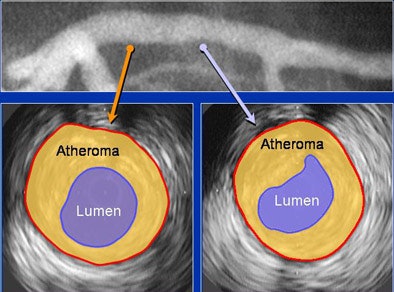

|

| Glagov remodeling, in which extraluminal plaque grows in volume while lumen size remains stable, is common in atherosclerotic disease. All images courtesy of Dr. Steven Nissen. |

He illustrated his point with a "normal" CT angiogram that showed a patent lumen but a huge extraluminal atheroma covering the coronary atrial tree. Next came a video of a ruptured plaque that oozed lipid material coursing down the coronary artery, causing a cascade of thrombosis in its wake.

"Coronary disease is not about intraluminal plaque -- it's about disease of the vessel wall," he said. "And any of those plaques can potentially fracture and cause an infarction. Stenoses don't kill patients, plaques do."

How prevalent is extraluminal disease? Well, today's atherosclerosis is not your grandfather's hardening of the arteries. Kids have it, too. One modality that can see the extraluminal plaque burden is intravascular ultrasound (IVUS). One IVUS study showed a disturbingly high disease prevalence in the hearts of young Americans.

Several years ago some of Nissen's colleagues in Cleveland, including Dr. E. Murat Tuzcu, conducted a preoperative IVUS assessment of 262 patients requiring heart transplants. Coronary artery assessment revealed that 17% of teenagers and 37% of those age 20-29 had IVUS-detectable atheromas.

"These findings suggest the need for intensive efforts at coronary disease prevention in young adults," Tuzcu and colleagues wrote (Circulation, June 2001, Vol. 103:22, pp. 2705-2710).

The group "saw individuals, some teenagers, that have large plaques in coronary arteries," Nissen said. "So the idea that we would focally be able to treat the vulnerable plaque is based on the concept that you can find a simple lesion in the coronaries -- when the fact is, by the time we see most of our patients, the disease is absolutely everywhere."

Whether or not stenosis or ischemia is present, most people carry a huge burden of disease, Nissen said. "Under the right circumstances, any of these plaques can rupture, causing acute coronary syndromes" (ACS), he said. "It's not about the vulnerable plaque; it's about the vulnerable patient."

As a result, stenting the vulnerable patient doesn't necessarily solve the problem. One patient at the facility, a 54-year-old man with unstable angina, underwent coronary angiography that revealed an obvious culprit lesion in the right coronary artery, which was stented. But stenting didn't solve the problem. IVUS showed a ruptured plaque. The lipid core was gone; from a coronary ulcer, a mix of blood and plaque flowed slowly down the artery. A second ruptured plaque could be seen in the right circumflex artery.

"That's the dominant feature of ACS," Nissen said. "Multiple studies have shown that when one plaque ruptures, there are often plaque ruptures at multiple other sites within the coronary arteries."

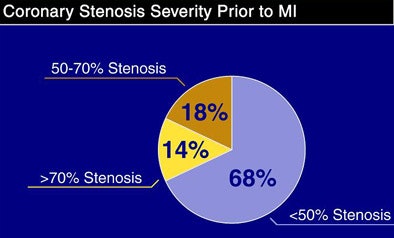

Most plaque ruptures occur in vessels without significant stenosis. And up to 80% of ACS patients have more than one plaque rupture, he said. Multifocal and systemic disease cannot be resolved by simply finding the critical plaque and fixing it.

"It's very tricky," Nissen said. "So many plaques do not narrow the lumen, so techniques designed to perform luminography may not be very useful at predicting who will and who will not have future coronary events" (Bhatt et al, Journal of Invasive Cardiology, March 2003, Vol. 15, Supplement B:3B-9B; discussion 9B-10B).

|

| A meta-analysis led by Dr. Erwin Falk (Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark) showed that low-grade stenoses cause most myocardial infarctions (MIs). |

And unfortunately, in ACS the plaque rupture is only the tip of the iceberg. Under the surface are any number of factors that can potentially cause catastrophic events in multiple plaques. In ACS, there is extensive vascular reformation. High levels of systemic inflammation are associated with multiple plaques, and there are hyperactive blood platelets in patients with ACS, Nissen said.

|

| Above and below, patients with normal or near-normal angiographic findings show extensive extraluminal plaque volume at IVUS. |

|

Another of Nissen's Cleveland Clinic colleagues, Dr. Stanley Hazen, has participated in several studies documenting the role of myeloperoxidase, a neutrophil-derived enzyme, and its major product, hypochlorous acid, in the pathogenesis of coronary artery disease, Nissen said. The researchers have found a strong association between myeloperoxidase levels and ACS (Baldus et al, Circulation, September 2003, Vol. 108:12, pp. 1440-1445).

Reggi et al serially examined 495 asymptomatic subjects with electron beam CT serially as they began statin therapy. The study showed that progression of coronary artery calcium was significantly greater in patients receiving statins who had a myocardial infarction compared with event-free subjects despite similar control of serum low-density lipoprotein levels. Statins may not prevent cardiac events in some patients, the authors concluded (Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, June 2004, Vol. 24:7, pp. 1272-1277).

So risk isn't only about the plaque, but rather what's happening in the blood, Nissen said. The risk depends on the environment in which the plaque exists. And systemic inflammation -- as anyone who's traded in a cheeseburger diet for wild salmon and green tea knows -- is a bad sign.

In another study, Kremer et al found that gadolinium contrast tends to remain longer in areas of fibrosis infarction or fibrous cap delineated from other components of plaque, facilitating lesion detection.

"My own view is that if you want to detect the vulnerable patient, imaging is not likely to be as useful as soluble biomarkers," Nissen said. "Most of this disease is silent; it's not intraluminal. You won't detect it at nuclear scintigraphy or exercise echo, and you won't detect it on CT angiography."

Therefore, the challenge for the future does not lie in detecting the presence or absence of stenosis.

"It's in developing methods of predicting how that plaque will behave," Nissen said. "That's why we've got to get beyond the concept of imaging plaque and understand the vulnerable patient and how all the factors come into play: platelets, white blood cells, inflammation -- and that's how we will ultimately make patients less vulnerable to these events that are so catastrophic."

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

December 7, 2006

Related Reading

Early coronary revascularization after MI cuts stroke risk, October 24, 2006

CT assesses plaque composition, but with difficulty, September 18, 2006

Plaque inflammation seen contralateral to symptomatic carotid stenosis, September 15, 2006

Multislice CT almost as good as IVUS in acute coronary syndromes, September 6, 2006

Statins appear to have no major effect on coronary calcification, August 29, 2006

Copyright © 2006 AuntMinnie.com