AuntMinnie.com is pleased to present an excerpt from The Death of Mammography by René Jackson and Alberto Righi, Caveat Press, Ashland, OR, 2006, ISBN 0-9745245-3-0.

History of breast cancer

Though often thought of as a more contemporary issue, cancer has been with us for thousands of years. At one time, people thought cancer was a product of industrialization, but archaeological finds would reveal the oldest specimen of cancer found in a human, which was discovered in the remains of a female skull from the Bronze Age (between 1900 and 1600 B.C.).

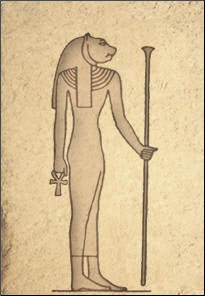

Although breast cancer has been around for thousands of years, treatment did not come about until recently and in ancient Egypt was practically nonexistent. The only "treatment" available subjected women to a barbaric type of surgery ending with cauterization (to stem blood flow) -- using boiling oil -- or a tool called a fire drill without the benefit of anesthesia or antisepsis. The Egyptians had a tendency to blame foreign gods for diseases and prayed to the god Bes and goddess Sekhmet to protect them. Because of the absence of a humane treatment for breast cancer, millions of women have died from the disease throughout history.

|

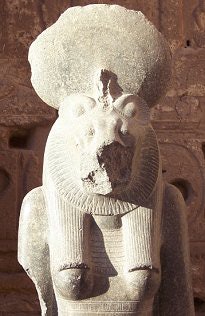

| Above, Sekhmet was seen as a goddess who could inflict disease as well as heal it. Ancient Egyptians prayed to placate her so that she would cure their illnesses. During Egypt's Middle Kingdom, Sekhmet was synonymous with doctors and surgeons. Below, a statue of Sekhmet at the Medinet Habu temple in Egypt. |

|

Breast cancer was known in other parts of the world, and the written records of most civilizations show reference to the disease. Writings from India dating back to approximately 2000 B.C. document the treatment methods of breast cancer as surgical excision, cautery, and arsenic compounds. Democedes, a Persian physician living in Greece between 484 and 425 B.C., was credited with the first recorded "cure" of breast cancer. The queen of Atos, wife of King Darius, is believed to have had breast cancer, which Democedes ostensibly cured without mutilating her breast.

We can trace the English word carcinoma to Hippocrates who first used this word as we think of it in modern terms in about 460 B.C. He used the words carcinos and carcinoma, from the Greek term karkinos, referring to a crab. Hippocrates probably likened the crab to a malignancy because of the shape of the projections spreading from a tumor reminded him of a crab. Furthermore, the word "cancer" means crab or crayfish in Latin.

Hippocrates also believed there needed to be a balance of four fluids in the body for a person to stay healthy: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Too much or too little of one, Hippocrates thought, would cause disease. And, if there was too much black bile accumulating at one or more body sites, this could lead to cancer.

***

The first-century Roman physician Aulus Cornelius Celsus knew that cancer usually recurs: "After excision, even when a scar has formed, none the less the disease has returned." Celsus wrote this about breast cancer, "We have often seen in the breast a tumor exactly resembling the animal the crab. Just as the crab has legs on both sides of his body, so in this disease the veins extending out from the unnatural growth take the shape of a crab's legs. We have often cured this disease in its early stages, but after it has reached a large size no one has cured it without operation. In all operations we attempt to excise a pathological tumor in a circle in the region where it borders the healthy tissue."

|

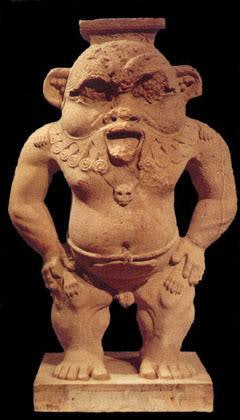

| Once depicted as a lion rearing up on his hind legs, the Egyptian god Bes ultimately morphed into a dwarf with some feline body parts. A figure of Bes was kept in a home to ward off evil, but also to facilitate fertility and good health. Image courtesy of www.egyptos.net. |

Celsus advised against surgery, cautery, and caustic medicines. Curiously enough, though the Romans knew nothing about the spread of disease per se, they always boiled their surgical "instruments" before starting an operation. The Romans modeled their medical practices on the Greeks, and the Greeks took what they knew from the Egyptians.

In A.D. 180 across the Aegean Sea in Greece, Leonides is credited with being the first physician to surgically remove a breast using a knife, and cautery to stem the flow of blood during and after surgery.

Also in the second century, Caudius Galen, a Greek physician, pharmacist, and philosopher from the isle of Pergamus, thought much as Hippocrates had. Galen came to Rome at a young age to establish his practice and became physician to the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

Galen believed breast cancer was caused by extreme depression and prescribed treatment with various herbs and special diets, and even exorcism. Though Galen said that once a patient was diagnosed with cancer there was no cure, he thought surgery could cure the cancer if the tumor was completely removed in its earliest stages.

***

In the middle of the third century during the reign of the Romans, a girl by the name of Agatha lived in Sicily. Beautiful and from a noble family, Agatha was noticed by the governor of the city, who wanted to possess her. Agatha refused in order to maintain her chastity. Enraged by her refusal, the governor treated her cruelly by ordering her breasts torn off with iron shears and then sent her to a dungeon to die. Roman Catholics believe God sent St. Peter to restore her breasts and heal her.

When the governor discovered this, he was furious and directed that Agatha be tied to a rack and burned over hot coals. As legend has it, an earthquake erupted, causing her captors to flee. Agatha survived this torture only to die from her wounds. She is known as the patron saint of breast cancer.

|

| In the story of her martyrdom, Agatha's breasts were cut off by a jealous courtier who would not accept her vow of chastity, and she became a patron for sufferers of breast cancer. Above, a 14th century bust of St. Agatha, who was martyred in Sicily in the third century. After years of outdoor weathering, this statuette was brought into the church at Lechlade, Gloucestershire, U.K., and placed in the north wall. Below, a reproduction of the painting "St. Agatha" by Spanish artist Francisco Zurbaran. Second image courtesy of New Crafts Co. |

|

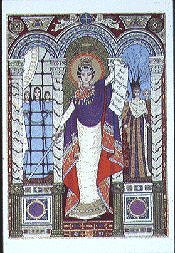

In the sixth century, a Byzantine princess named Theodora chose to live with her breast cancer rather than undergo disfiguring surgery and the subsequent suffering she knew it would have entailed. Theodora refused the torture of being awake during surgery -- because anesthesia had not yet been discovered -- while her breast and surrounding tissues were removed with crude instruments. She then would have had to endure the awful pain, not only during the relatively brief time of surgery but months, possibly years, afterward. In addition, just as today's women have to suffer deep psychological trauma related to mastectomies, Theodora, and the women of ancient times would have suffered most of the same symptoms, without the benefit of psychological help.

An Islamic surgeon born in Spain (1013-1106), Abulcassis thought surgery should be attempted only if the tumor was small and found in an early stage. He wrote that he had never been able to cure breast cancer, nor did he know anyone who had. He believed that before surgery was performed, the patient first had to be purged of bile and possibly have her veins bled.

In the European Dark Ages, surgeons were not highly regarded, nor were they very educated or even considered intelligent. The Middle Ages was a time of superstition regarding disease treatment, including treatment for breast cancer. The power of the Roman Catholic Church was a great influence on science; because of the church's influence, people of those times believed illness was a result of sin and a punishment from God.

|

| Theodora became a Byzantine empress when she married Justinian I. She was a champion for women's rights, establishing laws that allowed females to inherit property, and founded hospitals. She was diagnosed with breast cancer but declined treatment, which would have involved the surgical removal of her breasts. Image courtesy of Women's International Center. |

Scientists began to better understand the human body in the 15th century, when learning and medical teaching were revived. As an alternative to cauterization, Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) recommended sutures to control bleeding after mastectomy. Vesalius was a professor of anatomy at Padua University in Italy, and he urged physicians to understand the human body through dissection. Because the Church prohibited dissection, he often took bodies from graves and even stole from the gallows in secret. His book about anatomy, de Humani Corporis Fabrica, depicted the human body in greater detail than ever before recorded.

A second Renaissance figure, Ambrose Paré (1510-1590), discovered another alternative to cauterization when excising breast tumors: he mixed egg white, turpentine, and rose oil for a more effective and less painful way to seal a wound. He also substituted sulfuric acid for hot cautery. During this era several other topical treatments were used, including goat's dung, frogs, laying on of hands, and compression of the tumor with lead plates. Paré also knew that the axillary lymph nodes were usually part of the malignant process.

Breast cancer and surgery were studied in France, England, and Germany during the next few centuries and as far south as the Caribbean in the 1800s. In Germany, a barbaric instrument was discovered that was believed to reduce pain and speed up the time of surgery. The instrument held the breast at its base so a knife could swiftly amputate it. The Dutch and the French also discovered instruments of this type. Some of these instruments used forks and metal rings to hold the breast in place for amputation with a knife or a hinged scythe. However, this procedure created such large wounds that it sometimes took months to heal.

Lumpectomy and mastectomy were performed in the 17th century by the Dutch surgeon Adrian Helvetius, who believed surgery was a cure for cancer. Despite radical treatments for breast cancer over the centuries, documentation shows that some women went on to experience a normal recovery. In the year 1700, a nurse named Sister Barbara developed breast cancer, underwent a mastectomy, and lived another thirty years. It was believed, however, that even if a woman underwent a mastectomy, cancer was likely to recur within eight years, especially if there was glandular or lymph node involvement.

In the 17th through 19th centuries, physicians who studied breast cancer and performed mastectomy worldwide were mostly of the opinion that the entire breast should be removed (including the axillary nodes), in order to give the patient a greater chance of living a normal life. But most surgeons realized that if the cancer had spread this far -- the axillary nodes were removed -- chances of survival, or cure, were slim.

Charles Moore (1821-1879), a surgeon at the Middlesex Hospital in London believed in follow-up after breast cancer surgery, to effectively study survival rates. Moore realized there were many recurrences of breast cancer following surgery and reported several causes. He believed that breast cancer required extensive surgery to increase the chances of survival, and that recurrence of the disease were found near the scar, if the surgery was limited. Moore believed that during surgery, the whole breast should be removed, including diseased axillary glands, and he avoided cutting into the tumor.

Click image to enlarge

In the U.S. in the late 19th century, William Halsted, a professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, began using anesthesia, which first became available in 1846. He also used antisepsis, which became available in 1867, when performing radical mastectomy. Halsted believed surgery, which included removal of the breast, the underlying pectoralis major muscle, and axillary lymph nodes, was a cure. He also believed that if more tumors were discovered elsewhere in the body, they were new and different cancers. Halsted used a "tear-drop" incision, which later required grafting, because much of the skin was removed. Halsted is credited with perfecting the way radical mastectomy was to be performed in the next 100 years.

At the same time English surgeon Stephen Paget was studying the concept of metastasis. Paget's discoveries were confirmed more than 100 years later with cellular and molecular biology. The discovery that cancer cells spread by way of the bloodstream and make a new home in specific locations throughout the body, led scientists and researchers to surmise that surgery is not always the answer. They began to develop medications that would kill the malignant cells that had spread through the body. Many physicians, including William Sampson Handley of London, believed cancer originated at one point in the body and spread equally in all directions through the lymphatic system.

Handley advocated treating cancerous internal mammary nodes with interstitial radium. This treatment was continued by his son, Richard S. Handley, who biopsied internal mammary lymph nodes during mastectomy. Many surgeons during the time adopted Handley's treatment with radium. Though the recurrence rates were reduced with radical mastectomy, overall survival rates did not improve, most likely because by the time women underwent mastectomy, the disease had metastasized, and also because of the extremely high rates of infection. The survival rate for breast cancer in the 1800s was about three years.

During the 19th century, not only was it discovered that breast cancer was dependent on hormones in some patients, but it was observed that breast cancer growth, at times, fluctuated with the menstrual cycle and tumor growth slowed in women who were postmenopausal.

In 1878, Thomas Beatson, a graduate from the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, discovered that the ovaries, which produce the female hormones estrogen and progesterone, regulate the breasts, which contain estrogen receptor cells. In 1896, he found that patients with advanced breast cancer who had their ovaries removed sometimes showed improvement. After two of his patients underwent surgical removal of the ovaries, their tumors decreased in size. Beatson's work is the basis for today's hormone therapy, as well as the development of such drugs as tamoxifen.

Emil Grubbe, a homeopathic physician, born in Chicago in 1875, entered Hahneman Medical College in 1895, the year Roentgen discovered the x-ray. Impressed by Roentgen's discovery, Grubbe obtained a vacuum discharge tube and began experimenting with the fluoroscopic capabilities of the x-ray. Dr. Grubbe began to suffer from dermatitis of the hands and neck from the radiation, which spurred him into experimenting with radiation to treat cancer. He founded the first radiation therapy facility in Chicago in 1896, before graduating from medical school in 1898.

Grubbe performed the first medical irradiation for breast cancer on a patient named Rose Lee, who received 19 one-hour radiation treatments. Lee, however, died a month later from the cancer. Along with teaching at four educational institutions, Grubbe published extensively throughout his life. From the early 1920s to his retirement in 1947, he restricted his practice to radiation therapy. Grubbe's left hand was amputated in 1929, and he subsequently underwent surgery for skin cancer, and died in 1960 from squamous cell carcinoma that had metastasized.

Though radiation had been effective in treating breast cancer, some physicians believed radiation by itself should be used without surgery. Others thought radiation should always follow surgery. D. H. Patey and W. H. Dyson, of the Middlesex Hospital in London, introduced the modified radical mastectomy in 1949, and they encouraged radiation as an adjunct treatment to surgery. Another British physician, Robert McWhirter, encouraged simple mastectomy with radiation treatment, and his method yielded impressive survival rates compared to those of only radical mastectomy.

Rates of survival began to improve in the 1900s. Between the 1930s and 1950s, physicians were classifying the stages and progression of breast cancer, and the 10-year survival rates following radical mastectomy improved to roughly 50%. However, surgeons began to re-evaluate radical mastectomy, because of lymphedema, cancers induced by radiation, the disfigurement of the surgery itself, and the fact that they were unable to cure breast cancer in more that a third of the patients. Studies from the 1970s and 1980s show that breast-conserving therapy had similar results to mastectomy regarding control of local recurrence and overall survival rate.

With gains in knowledge about the biology of breast cancer, oncology, hormone therapy, and chemotherapy, survival rates began to improve for patients with high risk of recurrence. With the subsequent development and use of mammography, early diagnosis became a reality. The American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS) advocated more studies and trials in order to determine the efficacy of these various treatments.

The second half of the 20th century showed great gains in support for patients and research. In 1952, the American Cancer Society (ACS) began the Reach for Recovery program, which comprised a group of breast cancer survivors who'd had mastectomies. Their mission was to provide support for and serve as examples to newly diagnosed women, showing them that they, too, could go on with their lives after undergoing mastectomy.

Later in 1975, University of California researchers discovered that some genes in normal body cells could become abnormal, which led to the discovery of approximately 70 genes that can spur cancerous growths and at least a dozen genes that should deter such growth but do not. In 1994, Dr. Steven Narod, assistant professor in the Department of Medicine at McGill University in Montreal, discovered the breast cancer gene BRCAl, considered to be responsible for 2% to 4% of all breast cancer. The BRCA2 gene was discovered, and many more genes were identified in the years following.

Part of the history of breast cancer includes how it first became a sociological issue, then a political issue, and more recently, a legal one. Women from all walks of life have experience breast cancer including Abigail Adams, daughter of President John Adams in the 19th century; the mother of Louis XIV in the 17th century; and such contemporary public figures as Shirley Temple Black, Betty Ford, Linda McCartney, and Nancy Reagan.

Moving breast cancer into clinical and political focus, women banded together in the 1970s, after watching such famous figures come out into the open to publicize a disease originally treated as taboo. They showed that this disease crosses sociological lines and economic strata, and affects women of every race, religion, creed, and color.

In 1977, Rose Kushner, a breast cancer survivor who wrote the book Why Me? advocated that women should undergo biopsy first, to find out if the breast was cancerous, and then make their own decision regarding treatment. This was a progressive point of view, paralleling similar issues of patients' rights today. Ms. Kushner became a national figure and a spokesperson for women with breast cancer, and her supporters from Chicago started the national breast cancer support group Y Me. As public awareness of breast cancer increased, organizations began to spring up nationwide, breast cancer projects were started, and the government and politicians became involved. It was not until a few years later that the trial lawyers joined the battle, realizing how lucrative representing the plaintiff could be in a failure to diagnose breast cancer case.

Through the years of research and development, treatment options and survival rates improved considerably. Researchers and scientists have developed staging systems, made improvements in equipment, and discovered the breast cancer gene, yet a cure for cancer still evades us. In many ways, our perception about cancer has not evolved. There are people today who believe there is no cure for cancer, no matter the treatment. There are current schools of thought that promote early detection as a safety net, as though it were a cure. And just as we know now, some of the greatest figures in the history of medicine knew that, no matter the treatment, cancer can and sometimes does return.

By René Jackson and Dr. Alberto Righi

AuntMinnie.com contributing writers

October 12, 2006

Edwin Smith papyrus image courtesy of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons' Cyber Museum of Neurosurgery.

Related Reading

How the legal system stacks the deck against mammography, April 3, 2006

Book review: The Death of Mammography, January 24, 2006

Sidestepping screening: What factors make women avoid annual mammography? October 10, 2005

Copyright © 2006 Caveat Press