The location of the pancreas in the abdomen makes it well suited for ultrasound examination. However, the complex anatomy of the organ and surrounding tissues make evaluation a demanding task, and the ultrasound echo of even the normal pancreas varies widely from patient to patient.

The key to proper imaging and evaluation of the pancreas, then, is guided training followed by experience with a large number of exams under skilled surveillance. This article deals with the examination technique of the normal pancreas, and the ultrasound images accompanying it are samples from our daily work. A future article will cover ultrasound findings in common pathology of the pancreas.

Anatomy

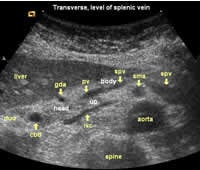

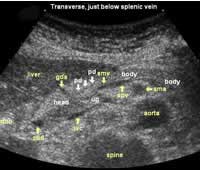

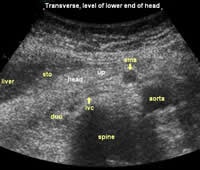

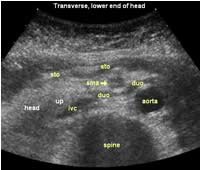

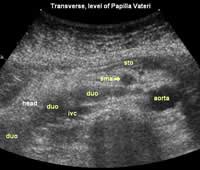

While an anatomic atlas is helpful for obtaining a detailed description of the morphology of the pancreas, I will also discuss the anatomic landmarks that are important from the sonographer's point of view. The pancreas is located in the epigastrium and has an oblong shape, oriented transversally across the midline. The main parts of the pancreas are the head with the uncinate process and the dorsal bud to the right, the body in the middle and the tail to the far left. The longest part of the pancreas is located to the left of the midline, with the tail near the splenic hilum usually slightly above the head. There are no clear demarcations between the different areas, though sometimes the dorsal bud of the head is darker, with sharp delineation compared to the rest of the pancreas.

The somewhat complicated shape of the pancreas, and its close relation to nearby structures, can make it difficult to determine when the entire organ has been covered by the exam. On the other hand, experienced sonographers learn to take advantage of the surrounding structures to identify and outline some of the borders of the pancreas. It is important and very helpful to recognize the most important and visible surrounding landmarks.

For ease of reading, I have used colloquial language whenever possible in the text of this article, basing the different directions and positions on the ground-reference anatomy of a person who is standing up. Hence, "above" means cranially, while "behind" means dorsally.

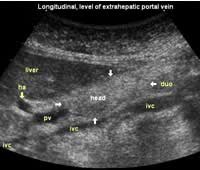

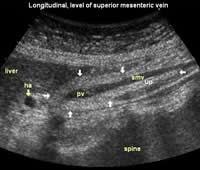

The dorsal aspect of the head takes the shape of a hook surrounding the right side of the superior mesenteric vein; the sharp left-pointing tip of the hook behind the vein constitutes the uncinate process. The splenic vein runs from the left along the dorsal border of the tail and body to the superior mesenteric vein, where these veins join to form the portal vein behind the "neck" of the pancreas. The portal vein then leaves the pancreas to the right and slightly upwards and runs into the liver hilum.

The main bile duct runs from the liver hilum to the right of and above the portal vein into the right dorsal part of the pancreatic head, where it runs vertically into the duodenum. The pancreatic duct typically runs along the body and tail to join the common bile duct near the duodenum. The gastroduodenal artery is sometimes seen in its position along the front margin of the pancreatic head, where it runs in a nearly parallel direction to the common bile duct. Like the common bile duct and pancreatic duct, however, the gastroduodenal artery is not always clearly seen due to its small diameter. The duodenum covers the right and bottom margins of the pancreatic head.

In practical terms, the structures mentioned so far are located more or less adjacent to the pancreas with no or a very thin layer of fat tissue in between.

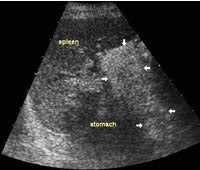

More or less fat tissue can be seen separating the pancreas from the following structures: The head and body of the pancreas are located below the liver, and below and generally behind the distal part of the stomach. The pancreatic head and body are located in front of the inferior vena cava and the aorta with the celiac trunk. To the far left, the tail of the pancreas has a position below the spleen and above the left kidney.

Study protocol

Pancreatic lesions are commonly presented only in the transverse plane, while other planes are sometimes omitted. This is probably due to the correlation to transverse CT scans, and the familiarity of pancreatic anatomy based on these exams. However, ultrasound has a unique strength in its ability to scan in almost any plane.

This advantage should be utilized, and to do so the sonographer must be familiar with pancreatic anatomy at different scanning angles. When scanning for lesions it is mandatory to use the longitudinal plane as well as the transverse plane on the pancreatic head and body. The pancreatic tail is not as easily accessible in many planes, but one can often get a good view through the spleen in the scan plane along the intercostal spaces, which often happens to align the transducer with the long aspect of the tail.

Echo of the pancreas

In addition to the demanding anatomy, there is a great variation in the appearance of normal pancreatic parenchyma. Generally the echo is quite homogenous, but it varies from a rather dark gray soft-tissue echo to a bright white echo that sometimes provides poor ultrasound penetration. The echo of the parenchyma is to an extent connected to the age and complexion of the patient, but not strictly so. Generally speaking, though, the older and more obese the patient, the brighter the appearance of the pancreas. With increasing obesity the pancreas tends to become more "dense" to ultrasound penetration.

Most pancreatic malignancies are dark. This, and the fact that the pancreas itself tends to be quite bright, puts ultrasound in an excellent position for finding and outlining pancreatic malignancies. This issue will be covered extensively in a future article.

Common mistakes

In my experience with radiologists studying ultrasound, there is a struggle during the first few months to get a feeling for examining the pancreas. Some pitfalls are more common than others. The inexperienced often encounter the following difficulties:

- Bright pancreases are difficult to spot when their echogenicity is equal to that of the surrounding fat. Conversely, sometimes the fat in the mesenteric root is mistaken for the pancreas. With experience, sonographers can recognize the difference in the texture of the bright pancreas parenchyma compared to fat tissue.

- Bright and very dense pancreases with a dorsal shadow are sometimes thought to be gas artifacts from the stomach, even when access is good.

- The right margin of the pancreatic head may be overlooked due to its close proximity to the highly variable duodenum.

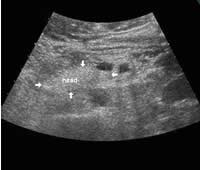

- The lower end of the uncinate process is often overlooked, probably because of its tapered form, which makes it blend with the surrounding fat tissue and the duodenum. Longitudinally, the head of the pancreas is often around 7 cm long, and pathology of the pancreas is often located in the difficult bottom area.

- The pancreatic tail is notoriously difficult to spot via the spleen, but with experience the texture of the pancreas becomes more evident, and very good views of the tail can be obtained in more than half of the patients. This view is particularly important for the evaluation of pseudocysts, which are quite common in the tail.

- Wide common bile ducts and pancreatic ducts are sometimes overlooked, and may be confused with the portal and splenic veins.

- Different patient positions may dramatically improve access to hidden parts of the pancreas. Students often try in the same supine position for too long, when an upright position or right or left decubital position could make all the difference. Also, experiment with different respiratory positions, as well as with a stretched or hunched back. It's unfortunate to have to do a CT scan just because the sonographer hasn't taken a few minutes to try different positions.

Examples

All of the material below show normal variations of the pancreas in patients with no apparent history of pancreatic disease. The still images were compiled especially for this article, since we usually do not archive still images except for illustrating measurements.

The following study describes anatomical landmarks in the ordinary pancreas of a thin patient:

Transverse planes in caudal direction:

Image01 |

Image02 |

Image03 |

Image04 |

Image05 |

Image06 |

Image07 |

Image08 |

Image09 |

Image10 |

Splenic view:

Image11 |

This study shows anatomical landmarks in the bright pancreas of a slightly obese patient:

Transverse planes in caudal direction:

Image15 |

Image16 |

Image17 |

Image18 |

Image18a |

Image19 |

Image20 |

Longitudinal planes from right to left:

Image21 |

Image22 |

Dark pancreas, slightly obese man:

Average echo, thin woman:

Average echo, normal body build:

Average echo, normal body build:

Rather bright pancreas, thin patient:

Almost isoechoic, normal build:

Isoechoic, obese patient:

Isoechoic, young obese woman:

Bright pancreas, clear dark dorsal bud (anlage):

Dense pancreas, obese patient:

Decubitus positions:

Right decubitus position:

Upright position:

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

December 17, 2002

Related Reading

Second-generation microbubbles enhance ultrasound's clinical utility, August 27, 2002

Copyright © 2002 AuntMinnie.com