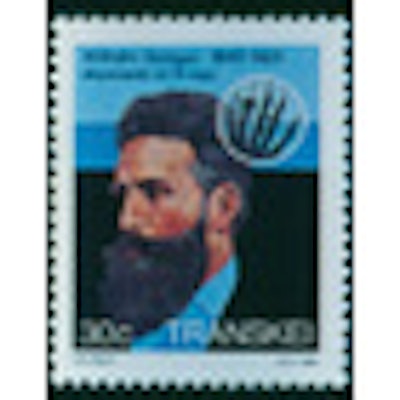

In early 1896, just after the birth of medical x-ray, doctors experimenting with the new rays realized that in addition to imaging bones, the technology was useful for the circulatory system. Their experiments -- many of which were daring by today's standards -- eventually led to the creation of a new medical subspecialty, interventional radiology.

In January 1896, two scientists in Vienna, Edward Haschek and T. O. Lindenthal, injected fluid calcium carbonate into the vessels of a cadaver's hand and produced an image showing the vascular system. In subsequent years, other doctors began injecting barium and other contrast agents into the blood vessels of living patients. The heart vessels and few of the veins and arteries could be seen.

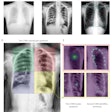

|

| Half-tone of a radiograph of the heart of a 47-year-old man, taken during full inspiration. The man was lying on his back on a stretcher, with the plate on the front of his chest. Image is from Roentgen Rays in Medicine and Surgery, 1903. |

In the mid-1930s, the efforts of Dr. George Robb and Dr. Israel Steinberg at Bellevue Hospital in New York City included injecting iodine-based contrast materials into the blood vessels of rabbits and then into humans in the spring of 1937.

"It was believed that opacification of the heart and lungs could be accomplished in this way (with intravenous injection of radiopaque substances)," they wrote in the January 1939 issue of the American Journal of Roentgenology.

"It was necessary to develop a technique which would permit injection of the radiopaque substance rapidly enough to make the blood stream opaque, and then to find a contrast solution which would be freely miscible with the blood, pharmacologically inert, nonirradiating to the vascular system, nontoxic in the dosage used, and rapidly inactivated or eliminated by the body," they wrote.

They continued to test their objectives until both of them joined military medical units during World War II. At the end of the war in 1946, Steinberg moved to New York Hospital, with a joint appointment in internal medicine and radiology. He continued his experiments, wrote dozens of papers, and trained several residents.

The most intent resident was Dr. Charles Dotter, who spent much of his time with Steinberg. During his residency, he became well-known for blood vessel imaging and was co-author of papers and a couple of books with his mentor. One of his major efforts was the manipulation of plastic catheters to be threaded through blood vessels near the heart; contrast media could be pressure-injected into the aorta or even a chamber of the heart.

After his residency, Dotter was appointed to the hospital staff and the Cornell University department of radiology. A couple of years later, he was recruited to be chairman of radiology at the University of Oregon in Portland, with the assurance that he could continue his research. Across the continent, he continued projects with Steinberg and maintained his joint manuscripts.

In the 1950s, Steinberg continued to train New York Hospital residents. In other countries, particularly in Sweden, radiologists adopted the Seldinger technique for percutaneous insertion of angiographic catheters. In the late 1950s, Dr. F. Mason Sones, a cardiologist at the Cleveland Clinic, perfected a technique of cine coronary angiography and injection into the coronary arteries. This allowed heart surgeons to see the site of vascular imperfections that needed surgical corrections to restore adequate heart circulation and bodily blood flow.

Shortly thereafter, Dotter accepted as an Oregon resident Dr. Melvin Judkins. In several years, Judkins devised a technique of injecting catheters with a spring wire through the femoral arteries of the leg to reach the heart. By that time, additional radiologists, including Dr. Herbert Abrams of Stanford University and young cardiologists with Sones, were working to improve techniques and treating heart patients.

Dotter had continued to manipulate catheters to correct coronary problems and inadequacies. One of his most famous devices was a catheter with a screw tip on the end. Some elderly people encountered blockages in leg arteries, which would lead to surgical amputation of toes and feet. The screw-tip catheter would be injected at the knee, pushed downward, and twisted to penetrate the arterial blockage, restoring circulation to the feet. The public attention over that technique brought him referrals from all over the U.S., as well as substantial donations from some of the corrected patients and their families.

The advances and improvement in cardiac and vascular injection of catheter-based contrast agents led interventional radiologists into fellowships to subspecialize in that technology. In later years, the American Board of Radiology offered an examination for subspecialty competence in interventional radiology diagnosis and treatments.

Otha W. Linton, MSJ, retired in 1997 as the associate executive director of the American College of Radiology (ACR) after 35 years. He also served as executive director of Radiology Centennial in 1995. Mr. Linton holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from the University of Missouri and a Master of Science in journalism from the University of Wisconsin. His work has been published widely in the U.S. and abroad, and he is a regular contributor to several journals including Academic Radiology, the American Journal of Roentgenology, Radiology, and the Journal of the American College of Radiology. He joined the ACR staff in 1961 and had a key role in its growth. Over the years, his responsibilities with the ACR included government affairs, public relations, marketing, publishing, industrial liaison, and international relations. Just before his ACR retirement, he became the executive director of the International Society of Radiology and continues in that role. Also, since his retirement, he has written and published 14 histories of radiology societies and academic centers.

Sources

Gagliardi RA, McClennan BL. A History of the Radiological Sciences: Diagnosis. Reston, VA: Radiology Centennial Inc.; 1996.

Greene J, Linton, OW. The History of Dotter Interventional Institute: 1990-2005, Portland, Oregon. Portland, OR: Oregon Health and Science University; 2005.