Retained surgical items after surgery can be a significant source of mortality, morbidity, and cost. Computer-aided detection (CAD) technology can help prevent these costly errors, however, according to a group from the University of Michigan Health System.

By combining a microtag placed on potentially retained foreign objects during surgery with the use of internally developed CAD software to spot these items on radiographs, the researchers believe more than 99% of retained surgical items could be detected.

"The number of cases missed by the CAD and discovered by the radiologist is so small, we anticipate it would be imperceptible during the career of a surgeon," lead author Dr. Theodore Marentis told AuntMinnie.com.

The researchers presented their experience at the recent SPIE Medical Imaging 2014 conference in San Diego.

Costly errors

Retained surgical items have been associated with approximately 4.5% mortality and 16% permanent disability, and burden the U.S. healthcare system with $1.5 billion a year in entirely preventable expenses, Marentis said.

The reported incidence of retained surgical items ranges between 1 in 1,000 and 1 in 8,000 surgeries, and each incident costs approximately $450,000 in preventable combined medical and legal expenses, he said.

Retained surgical items are "clear-cut cases of negligence, and malpractice caps do not apply," he said.

Radiographs are commonly used to detect retained surgical items, but they yield less than 60% sensitivity, he said.

"The reason [retained surgical items] are so often missed even by skilled radiologists, we believe, is because their radiopaque (x-ray visible) elements or filaments are deformable and are not standardized across vendors," Marentis said. "Their shape changes and creates a perceptual barrier for the radiologist, who may misinterpret the finding as a garment or external to the patient. A large part of the problem is the defective nature of surgical sponges and towels as highly variable detection targets."

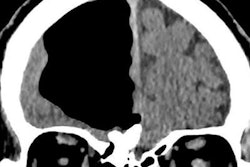

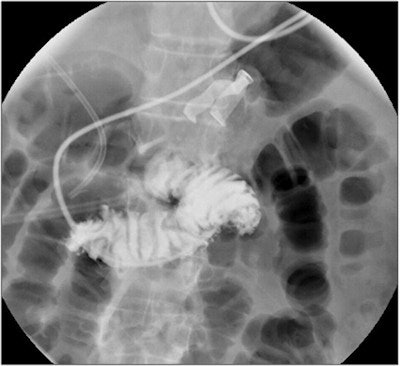

A surgical retained foreign object in plain sight during feeding tube positioning under fluoroscopy. Image courtesy of Dr. Theodore Marentis.

A surgical retained foreign object in plain sight during feeding tube positioning under fluoroscopy. Image courtesy of Dr. Theodore Marentis.Microtags and CAD

Seeking to improve on this situation, the University of Michigan team developed a method that employs microtags and CAD software. Codeveloped with the Chronis Lab in the university's bioengineering department, the microtag is visible on radiographs, doesn't change its shape, avoids high-contrast anatomical features, and produces a similar 2D projection regardless of orientation in space, Marentis said.

CAD software codeveloped with the department of radiology's CAD Research Laboratory then detects the microtags on radiographs using machine learning techniques. The CAD system includes six task-based processing modules for preprocessing, target enhancement, candidate labeling, segmentation, feature analysis, and classification. Detected tag locations are then highlighted on the radiographs for the radiologist to review.

The CAD software can operate in a "high-specificity" mode for the operating room and point-of-care applications, reducing turnaround time for intraoperative radiographs from 12 to 15 minutes to less than five minutes, he said. It can also run in a "high-sensitivity" mode, allowing the radiologists to identify all retained surgical items while easily discarding false-positive results, Marentis said.

In testing on a large database of cadavers, standalone CAD sensitivity was 93.5% with 0.36 false positives per image in the high-sensitivity mode and 82% with 0.004 false positives per image in the high-specificity mode for operating room use, according to the researchers. With a radiologist reviewing the CAD results, sensitivity reached more than 99%.

"It can eliminate a costly, entirely preventable surgical complication and keep patients safe," Marentis said.

Failing status quo

Marentis noted that the current clinical practice in 90% of U.S. hospitals to prevent retained surgical items is to perform a surgical count followed by a radiograph if the count is off. However, documented surgical counts were mistakenly thought to be correct in more than 90% of confirmed retained surgical item cases, he said.

"Therefore, the count is not accurate, and a radiograph is never acquired to augment it," he said. "The clinical status quo fails to address the pressing clinical need."

Approximately 10% of hospitals have tried to use barcode and radiofrequency technologies to improve detection of retained surgical items, but these require a change of clinical practice and retraining of the operating room staff. The lack of evidence-based outcome data and also the high cost and complexity associated with these approaches have so far prevented wider adoption, Marentis said.

"In contrast, with the proposed approach, a radiograph would be reimbursed $41 by CMS [Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services], while a surgery costs at least $10,000," he said. "The cost-benefit analysis of the microtag and CAD combination approach appears quite favorable."

In the next phase of the group's work, the team plans to further validate the CAD software in a cadaveric database and with healthy volunteers. They would also like to pilot the technology in an operating and extend the CAD methods to detect other objects, Marentis said.