Radiofrequency ablation (RFA), which uses heat to destroy cancerous tissue, may offer some lung cancer patients an alternative to extensive surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, according to a study performed at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

At last week's American Roentgen Ray Society meeting in San Diego, Dr. Franklin Liu from the institute presented the initial clinical results of patients who underwent the procedure at Dana-Farber. The team also included physicians from Boston's Brigham and Women’s Hospital, as well as from Harvard Medical School.

"Radiofrequency ablation can ease pain, slow tumor growth, and even destroy tumors in patients with advanced lung cancer," Liu said.

The group treated 12 patients ranging in age from 29-82 years. The patients had been referred to the group by oncologists, and were evaluated and considered unfit for operations by surgeons. All of the patients had exhausted radiation and chemotherapy treatment alternatives for their cancers.

Liu reported that nine of the patients had primary bronchogenic carcinoma without extrathoracic spread. Two of the patients presented with painful metastases, one from adenoid cystic carcinoma, and the other from metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue. The final patient of the group had metastatic colon cancer. The size of the tumors ranged from 3.5-5.5 cm with a mean tumor size of 4 cm.

"In nine of our patients, our goal was to destroy or slow the growth of their tumors; we also treated three patients to relieve their pain," he said.

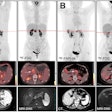

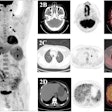

All of the patients were imaged with a combination of modalities, including x-ray, CT, PET, MR, and ultrasound before the RFA procedure. "Imaging with these modalities allows us to accurately gauge the extent of the disease and permits us to be as precise as possible in the treatment," Liu said. During the RFA procedure, CT or ultrasound is used by the interventionalist for probe guidance.

The patients underwent general anesthesia for the extent of the procedure, and an anesthesiologist was part of the treatment team during the procedure. The RFA was performed with a multipronged, 17-gauge array-type probe with an array diameter of 2-3 cm and a length of 12-15 cm.

"We used a variety of interventional radiology techniques to assist (in) the ablation procedure," Liu said. "They included inserting fluid to move the lung so we can better access the tumor, temporarily collapsing a lung to more safely treat the tumor, simultaneous dual ablation to treat the primary tumor and spread of cancer to adjacent ribs, and ablation to kill nerves near the tumor to alleviate the patient’s pain."

One technique the team used in providing RFA to some patients was the salinoma technique, which involves injecting a saline solution into the extrapleural tissue.

"This was very useful in treating patients with emphysema because of the possibility of their developing a pneumothorax during the procedure," Liu said.

In fact, despite the team's diligent efforts to prevent pneumothorax during the RFA, two intraprocedural pneumothoraces were reported. These were treated intraprocedurally with a small-bore, 7-French percutaneous catheter that allowed the procedure to continue.

The total RFA application time ranged from 18-37 minutes, and the patient was kept in the hospital overnight for observation. The researchers performed post-procedure follow-up imaging with chest x-ray, CT, MR, and PET.

Liu said that extensive necrosis was seen in all the treated tumors, and was manifested as no enhancement on the postprocedural contrast-enhanced MR images. Recurrent or persistent tumors were demonstrated by enhancement and nodularity on MRI or via increased FDG uptake on PET scans.

Complications as a result of the RFA procedure were minimal, according to Liu. One patient had a small area of burn adjacent to the probe entry site, and was treated during the overnight hospital stay.

The patients have been tracked for up to two years, with 10 of them still alive. Of the three patients treated primarily for pain control, all have reported significant reduction in their pain.

"We currently use radiofrequency ablation when the other forms of treatment such as surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy haven’t worked, won’t work, or if the patient requests this type of treatment," Liu said. However, a team of oncologists, thoracic surgeons, anesthesiologists, and interventional radiologists evaluates all patients and must concur for the RFA treatment to be employed, he added.

"Our study shows that imaging-guided RFA can successfully ablate lung tumor tissue with a reasonable margin of safety, and that it may offer a viable alternative for patients who cannot be treated or have failed other forms of treatment," Liu said.

By Jonathan S. BatchelorAuntMinnie.com staff writer

May 14, 2003

Related Reading

Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation may be an option for solid renal masses, April 21, 2003

Laser ablation of liver metastases boosts long-term survival, March 7, 2003

Radio-frequency ablation effective for many renal cell carcinomas, January 29, 2003

Radiofrequency appears superior to cryosurgery in preventing liver metastases, January 3, 2003

Intraoperative RFA has advantages over percutaneous technique, February 9, 2002

Copyright © 2003 AuntMinnie.com