DENVER - SPECT scans show changes in cerebral blood flow in retired professional football players that differ based on which position they played, according to researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The findings were presented on Monday at the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) meeting.

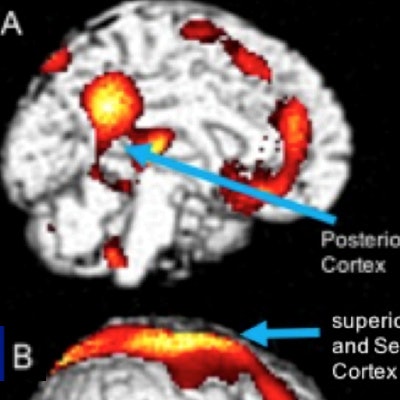

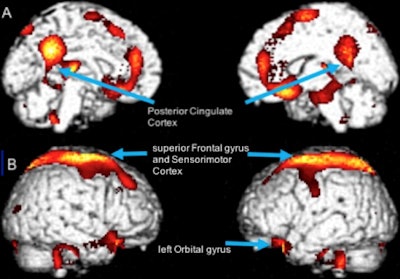

More specifically, spatial ability among former offensive linemen was related to left associate cortical blood flow, while the spatial ability of former defensive backs was associated with right posterior cingulate cortical blood flow. Those and other differences between the on-the-field positions could be related to the severity of concussions or traumatic brain injuries experienced by the players during their careers.

"Spatial ability in defensive backs, who tended to have fewer mild traumatic brain injury episodes but a higher frequency of loss of consciousness, correlated with posterior cingulate cortex [changes]," said senior author Dr. Dan Silverman, PhD, head of UCLA's neuronuclear imaging section. "In a direct comparison between the two positions, offensive linemen had greater activity in the sensorimotor and superior frontal cortex than the defensive backs."

Accumulating evidence

An increasing number of studies in recent years have raised concerns about mild cognitive impairment in athletes who experience repeated minor brain trauma. The issue has been highlighted in research using neuroimaging to find changes in brain structure and blood flow in people who participate in contact sports such as football, soccer, and hockey.

In an April 2016 study published in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, this group of UCLA researchers described regionally specific changes in brain perfusion patterns in 161 professional football players. On average, the subjects showed lower blood flow in 36 brain regions, particularly in the anterior superior temporal lobes, rolandic operculum, insula, superior temporal poles, precuneus, and cerebellar vermis, which are associated with memory, mood, and learning. The researchers also noted that 83% of the players experienced memory problems and 29% had a history of depression.

In the study presented at the SNMMI meeting, the researchers examined correlations between clinical symptoms and changes in blood flow among former professional football players who had been on an active roster for at least three years and played at either the offensive lineman or defensive back position. The 25 former offensive linemen (mean age, 56 ± 3 years) and 20 former defensive backs (mean age, 60 ± 2 years) all had experienced typical patterns of head trauma on the field. In addition, 25 normal controls were matched for age and other demographics with the players.

During their careers, the former players experienced mostly grade 1 concussions, including symptoms that lasted for fewer than 15 minutes. Grade 2 concussions involved symptoms that persisted for more than 15 minutes, while grade 3 concussions included a loss of consciousness. The former offensive linemen were more prone to grade 1 concussions.

| No. of concussions among football players | ||

| Type of concussion | Offensive linemen | Defensive backs |

| Grade 1 | 31.2 (± 7.7) | 13.8 (± 4.5) |

| Grade 2 | 1.1 (± 0.4) | 1.3 (± 0.5) |

| Grade 3 | 1.5 (± 0.5) | 2.2 (± 1.0) |

"Although there was almost double the number of traumatic brain injuries among offensive linemen, they tended to be more minor but less frequent than those that involved a loss of consciousness, compared to the defensive backs," said Silverman, who also serves as director of UCLA's Brain Wellness and PET Consultation Services.

As part of the study inclusion criteria, no subjects could be taking psychoactive medication. If they had done so in the past, there had to be an adequate window of washout to participate in the study. The same stipulation applied to the healthy control patients at the time of their assessments, who also had to have no history of brain injury or trauma or related medical problems.

All subjects underwent a technetium-99m (Tc-99m) hexamethyl propylene amine oxime (HMPAO) SPECT scan with a three-headed gamma camera as they performed attention-focusing cognitive tasks based on the MicroCog Assessment of Cognitive Functioning, which evaluates cognitive status in five areas: attention, memory, reasoning, spatial ability, and reaction time.

The MicroCog results from the athletes were compared with those from the healthy individuals, Silverman said. In addition, regional patterns of blood flow in the brain of each participant were assessed by standardized volumes of interest (sVOIs) and statistical parametric mapping (SPM) methods.

When Silverman and colleagues pooled the former NFL players' images and compared the results to the controls, the most notable differences in regional cerebral blood flow were seen in the posterior cingulate cortex and the sensorimotor cortex. The same blood flow patterns were evident when the researchers separated the SPECT images of the offensive linemen and defensive backs and compared the results to the healthy controls.

SPECT identifies brain regions of significant hyperfusion in former football defensive backs (A) and offensive linemen (B), compared with normal controls (right). Image courtesy of Dr. Dan Silverman, PhD.

SPECT identifies brain regions of significant hyperfusion in former football defensive backs (A) and offensive linemen (B), compared with normal controls (right). Image courtesy of Dr. Dan Silverman, PhD.When the researchers combined the SPECT images with the cognitive performance scores, there was a significant correlation between spatial ability and blood flow in the right posterior cingulate cortex among the defensive backs (p = 0.0003), but no such finding in the offensive linemen (p > 0.05). Conversely, there was a significant correlation between spatial ability and blood flow in the left associate visual cortex among the offensive linemen (p = 0.0006), but not among the defensive backs (p > 0.05).

The findings suggest that playing professional football is "associated with position-specific correlations between regional cerebral blood flow and neuropsychological measures," the researchers wrote. Silverman cited several limitations of the study, however, including the small sample size of 70 subjects who were distributed among three groups.

"Although that [total] is larger than other position-specific analyses, we still have to be very cautious about the generalizability of these findings to other groups of NFL players who are no longer athletes until we have an independent replication of those groups," he added.