Radiologic issues in lung transplantation for end-stage pulmonary disease.

Erasmus JJ, McAdams HP, Tapson VF, Murray JG, Davis RD

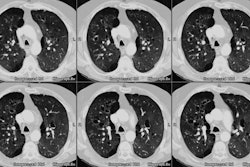

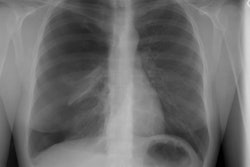

Lung transplantation has evolved into an effective therapy for end-stage pulmonary disease. The radiologist has an important role in the management of these patients before and after transplantation. Unfortunately, the radiologic findings of the major complications (i.e., reperfusion edema, infection, rejection) that occur after transplantation overlap and are often nonspecific. Clinical correlation, bronchoalveolar lavage, and transbronchial biopsy are usually required for accurate differentiation. The following rules of thumb may be helpful: Radiographic opacities seen during the first week are usually due to reperfusion edema: persistent or progressive opacities beyond the first week suggest infection or acute rejection: infection in the first month is usually bacterial, and opportunistic pneumonia is more common thereafter, nodular opacities are usually due to infection or posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders but can also be due to transbronchial lung biopsy; and progressive bronchial dilatation and air trapping seen on expiratory CT are useful signs of BOS.