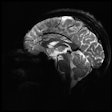

A new University of Vermont (UVM) study published in the February Journal of Pediatrics used MRI to connect concussions sustained by young ice hockey players with subtle changes in the outer layer of the brain that controls higher-level reasoning and behavior.

As the severity of the concussion symptoms increased, the cortex became thinner than what is considered normal at that age, the researchers found. The abnormality is particularly troublesome because the thinning of the cortex occurred in areas associated with attention control, memory, and emotions.

While the long-term effects of the thinning cortex are unclear, lead author Matthew Albaugh, PhD, and colleagues fear that the condition may be a harbinger of future brain damage, and that such an injury to a young, still-developing brain could have more severe consequences than a similar injury to an adult brain (J Pediatr, February 2015, Vol. 166:2, pp. 394-400).

Concussion frequency

Sports-related concussions and the long-term effects of head injuries have drawn increasing attention in recent years for professional, collegiate, amateur, and youth athletes. According to a 2013 "Ice Hockey Summit II" report, there are more than 300,000 sports-related concussions across all sports on all levels in the U.S.

Albaugh and colleagues cited research that suggests cerebral concussions account for 15% to 22% of all reported injuries in young male hockey players.

For their study, the UVM researchers recruited 29 males from preparatory school and collegiate ice hockey teams between 14 and 23 years of age (mean age, 17.8 years). Of the 29 subjects, 27 underwent both baseline neuroimaging and cognitive testing between July 2012 and June 2013. Two individuals were unable to complete cognitive testing.

Concussion histories were available for all 29 athletes. Among the 29 subjects, 16 reported having one to four concussions, with a mean of 2.1 concussions. All athletes were at least three months removed from their most recent concussion, with a mean of 40.6 months.

MRI exams were performed on a 3-tesla scanner (Achieva TX, Philips Healthcare) with an eight-channel head coil. For cognitive testing, Immediate Postconcussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing (ImPACT) was used to assess verbal and visual memory, processing speed, reaction time, and impulse control. ImPACT includes a scale of 22 commonly reported concussion symptoms, which are rated for severity using a seven-point Likert scale, resulting in a total symptom score (TSS).

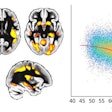

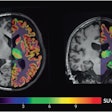

In reviewing structural MR images and the ImPACT results, the researchers found an inverse association between TSS and cortical thickness. The cortex was thinner in the frontal, parietal, and temporal regions of the brain in subjects with greater self-reported postconcussion symptoms, according to the authors.

The figure shows the inverse relationship between postconcussive symptoms and cortical thickness. Blue regions indicate where this relationship was statistically significant. Image courtesy of the University of Vermont.

The figure shows the inverse relationship between postconcussive symptoms and cortical thickness. Blue regions indicate where this relationship was statistically significant. Image courtesy of the University of Vermont.Interestingly, concussion history was not associated with cortical thickness. Albaugh and colleagues speculated that "reduced thickness in frontotemporoparietal areas may be tied to more subtle, repetitive blows to the head as opposed to discrete concussive episodes." It is also possible that the hockey players were incorrectly recalling their concussion history, they added.

The UVM researchers plan to follow the study's athletes over the next couple of decades to see if and how their participation in hockey as well as other lifestyle factors, such as smoking and alcohol use, affect their brains.

They also want to apply the current study to female and male ice hockey players ages 8 to 14 years, college-age skaters of both genders, and retired professional hockey players. They hope to compare the findings for each age group to nonathletes and to similar groups in soccer, where players have less-severe head injuries.

The authors cited several limitations of the study, including its relatively small sample of athletes, and the fact that concussion history was based on retrospective self-reporting. In addition, it is possible that the postconcussive symptoms were not related to repetitive head trauma, they noted.

Hyperintensity factor

Results of a follow-up study from UVM also suggest that a greater volume of hyperintensities is associated with decreased thickness in the cortex.

Hyperintensities appear as small, bright white spots on MR images. Previous studies unrelated to the UVM research have linked hyperintensities with cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease.

People generally accumulate one hyperintensity for every 10 years of life, Albaugh noted in a statement from the university; for example, a 50-year-old individual would have about five hyperintensities. Yet one college-age athlete in the study had 18 such hyperintensities.

Such results have prompted Dr. James Hudziak, senior author of the studies and director of UVM's Vermont Center for Children, Youth, and Families, to call some parents to tell them of the "clinically concerning findings" in their children's brain images.