Lung cancer screening has been known to improve survival among individuals diagnosed with lung cancer for more than 25 years. Three studies conducted by the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) at the Mayo Clinic, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and Johns Hopkins during the 1970s each showed survival of approximately 50% in individuals with lung cancer diagnosed in chest x-ray screening plus cytology, compared with 20% or less among symptomatic cases in the population.

Similar improved survival and reduced mortality were recorded in five large Japanese case-control studies. NCI epidemiologists insisted that improved survival was spurious, caused by lead-time, length-time, and overdiagnosis biases, and recommended that population screening not proceed until evidence from randomized, controlled trials showed mortality reduction.

On October 28, 2010, NCI Director Dr. Harold Varmus halted the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) when it achieved a lung-cancer-specific mortality reduction of 20% (7% all-cause mortality reduction) with "no unforeseen screening effects" (risks). Varmus emphasized that it would be unethical to continue the trial, and explained that because CT screening was only conducted for two years in NLST, further follow-up would be uninformative.

Despite the stellar results of NLST, some critics persist in cautioning delay, insisting that the benefit-harm balance and cost-effectiveness modeling must first be assessed. These assessments have resulted in widely varying estimates of risk-benefit ratios and costs that have, in turn, resulted in varying guidelines and payment decisions with further delays in implementation.

It is axiomatic that if the benefits of CT screening are underestimated and the risks are exaggerated, then any statistical model of screening will generate low cost-effectiveness. Injudicious conclusions based on inaccurate data will predictably result in adverse guideline recommendations and payment decisions that will delay, restrict, minimize, or deny access to screening. Unfortunately, this is precisely what has happened in recent months.

Incorrect estimates

In my opinion, the benefit of screening has been incorrectly estimated. Bach et al in a recent "systematic review" in the Journal of the American Medical Association conclude that only one in five people with lung cancer detected by CT screening are cured; 80% die. Under this model, 320 individuals must be screened to save one life.

These numbers are grossly inaccurate. In fact, survival of study subjects at five and 10 years in the International Early Lung Cancer Action Program (I-ELCAP) and in numerous other prospective screening series in the U.S., Europe, and Japan consistently exceeds 80%: i.e., four of five patients are cured. None of this data was included in the JAMA publication.

Thoracic surgeon Dr. Frederic Grannis Jr.

Thoracic surgeon Dr. Frederic Grannis Jr.Similarly, the risks of lung cancer screening have been grossly inflated. The incidence of false positives in NLST is reported as 50% or more in the first two rounds of screening, but the comparable 20% figure in I-ELCAP was not noted. The difference reflects the strength of I-ELCAP's diagnostic algorithm and the absence of a comparable protocol in NLST.

American Cancer Society CEO Dr. Otis Brawley has stated that screening complications were the cause of death of 16 study participants within 60 days of a diagnostic procedure conducted in NLST. In actuality, there is no documentation that a single death was caused by an NLST screening complication. In addition, there were no deaths following surgical resection of a benign lesion in the I-ELCAP experience of more than 60,000 screened individuals.

How is it possible that such inaccurate estimates found their way into a "systematic" review sponsored by prestigious professional societies? First, only a small fraction of available evidence was analyzed. The exclusion of 194 of 198 peer-reviewed publications from I-ELCAP investigators suggests a systematic bias in the selection of the review's evidence base.

Furthermore, the senior author, Dr. Peter Bach, has a remarkable track record of inaccuracy in prior manuscripts and media comment. Space limitations allow inclusion of only a few examples.

"Ours is the first study to ask whether detecting very small growths in the lung by CT is the same as intercepting cancers before they spread and become incurable," Bach stated. "We found an answer and it was, 'NO.' "1

"We saw 10 times as many surgeries being done because of the CT scanning," he said. "And no one's life was saved. Not one case of advanced cancer was prevented."2

"In fact, people who get CT scans are 100 times more likely to get a false alarm than they are to die of lung cancer."3

If the stakes were not so high, such repetitive, gratuitous error might be risible, but a number of guideline groups -- the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) -- have accepted Bach's assessments unquestioningly and recommend that lung cancer screening be restricted to individuals who meet the NLST entry criteria: i.e., smokers age 55 to 74 and ex-smokers who had quit not more than 15 years ago, with more than 30 pack-years of cigarette smoking.

Impact

Following an October 19, 2012, meeting in South San Francisco, CA, between the California Technology Assessment Forum (CTAF) and Blue Cross of California, at which Bach presented his findings, Blue Cross decided to cover only individuals meeting NLST criteria.

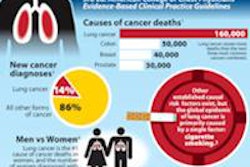

"The impact of screening using NLST criteria, even if widely applied, would have a relatively minor effect (estimated 2-3,000 fewer deaths) on the 160,000 deaths from lung cancer in America each year," concluded CTAF Chair Dr. Dan Ullyot. This is absurdly low. An actuarial study from consulting firm Milliman suggests that 76,000 lives might be saved by population screening.

Restricted insurance coverage excludes a large majority of those at risk of lung cancer, including many ultrahigh-risk individuals. Specifically, people with a prior lung cancer are not included, despite the fact that Bach himself recently co-authored a manuscript documenting enormous lung cancer risk in such patients.

Readers can go to the Memorial Sloan-Kettering website and use Bach's own lung cancer risk estimator to demonstrate that many individuals, including younger people with heavy smoking experience and workers with industrial exposure to carcinogens, have documented risk substantially higher than that of NLST participants.

Also excluded are healthy individuals older than 74 who have substantially higher risk. The Blue Cross of California decision to adhere to NLST criteria hamstrings the potential of screening to save thousands of lives by institutionalizing potentially lethal disparities.

Upcoming USPSTF decision

These disparities pale in significance compared to the harm that will occur if the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) decides to recommend against or restrict access to lung cancer screening. Some background is in order.

The USPSTF is a committee of individuals -- none of whom have personal experience or expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer -- who are charged with advising Congress whether Medicare and Medicaid should pay for screening tests.

The group relies on evidence summaries presented to it by others. If the evidence provided to USPSTF is limited only to NLST and redacted data contained in the JAMA article that omits results of screening from multiple other relevant sources, USPSTF members might recommend against lung cancer screening. This would result in the underprivileged and elderly -- those without financial resources to pay for screening out of pocket -- remaining unscreened and continuing to get treatment only for symptomatic lung cancer, with inevitable progression and death in 85% of cases.

Is such concern paranoiac? Many experts don't think so. Recent USPSTF decisions resulting in recommendations against mammographic screening of women younger than 50 and against prostate cancer screening have resulted in widespread criticism.

The palliative against a misguided and disastrous recommendation is obvious. The evidence base relied on by USPSTF must be publicly available, and when omission of pertinent evidence is identified, there must be a transparent mechanism to ensure that such evidence is not redacted from the USPSTF guideline process.

When guideline groups pay heed to all of the evidence, they make judicious decisions. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) has extended screening eligibility to high-risk individuals up to 79 years of age. Experienced clinicians expert in lung cancer diagnosis and treatment from 20 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) centers have crafted a guideline recommending that screening eligibility extend down to age 50 in individuals with other risk factors and up to older patients, without an upper age limit.

USPSTF has not updated its "I" rating of lung cancer screening (insufficient evidence) in the nine years since 2004. An update is expected to be announced in the near future.

Although Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Director Dr. Carolyn Clancy stated in 2011 that she anticipated a draft statement on lung cancer screening from USPSTF in 2012, none was forthcoming. Clancy later pushed back the time of such a statement to early 2013, and Dr. Virginia Moyer, the USPSTF chair, later commented that the review would be completed "in 2013."

It is known that multiple organizations, including the Lung Cancer Alliance, Legacy Foundation, and Prevent Cancer Foundation, have written to Health Secretary Kathleen Sebelius complaining of "unconscionable delay" in a USPSTF guideline update.

The organization's failure to make a timely, favorable, and inclusive recommendation to Congress for Medicare and Medicaid coverage of population screening of high-risk smokers and ex-smokers would be cruelly irresponsible for hundreds of thousands of Americans with lung cancers growing inside them -- today -- who will otherwise inevitably suffer and die of lung cancer.

References

- Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Study shows no benefit for CT screening for lung cancer. http://www.mskcc.org/mskcc/html/74428.cfm. Published March 6, 2007. Accessed May 31, 2013.

- Knox R. Study questions early screening for lung cancer. National Public Radio. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=7744559. Published March 7, 2007. Accessed May 31, 2013.

- Szabo L. Using CT scans to screen for lung cancer may carry risks. USA Today. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/health/2009-05-30-CTscans-lungcancer_N.htm?csp=34. Published May 30, 2009. Accessed May 31, 2013.

Dr. Frederic Grannis Jr. is a clinical professor of thoracic surgery and president of the medical staff of City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, CA. His primary clinical and research interests have been in the prevention, early diagnosis, treatment, and supportive care of patients with diseases caused by tobacco products. His interest in lung cancer screening extends back to surgical treatment of patients as a resident at the Mayo Lung Clinic in Rochester, MN, during the 1970s. His clinical experience and research results convince him that the best hope to reduce suffering and death from lung cancer lies in tobacco control public policy, smoking cessation, and screening.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnie.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular vendor, analyst, industry consultant, or consulting group.