Five minutes in an MRI scanner can reveal how far a child's brain has developed from childhood to maturity, and it may shed light on a range of psychological and developmental disorders, scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found.

A study published in the September 10 issue of Science suggests that brain imaging data can offer more extensive help in tracking aberrant brain development. Researchers found that a new method of evaluating brain scanning data may be able to provide similar guidance for monitoring and treating patients with psychiatric and developmental disorders (2010, Vol. 329:5997, pp. 1358-1361).

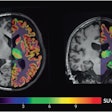

Senior author Bradley Schlaggar, MD, PhD, a pediatric neurologist and associate professor of neurology, and colleagues used a resting-state functional connectivity MRI scan. By correlating increases and decreases in blood flow to the various brain regions as subjects rest in the scanner, it can be determined which of these regions work together in brain networks.

When functional data are compared to standardized models showing how brains function or diseases normally develop, a range of new clinical insights becomes available, according to Schlagger. "Data is typically looked at from a structural point of view, identifying what is different about the shapes of various brain regions," Schlagger said. "But MRI offers ways to analyze how different parts of the brain work together functionally."

In a recent study, Washington University scientists showed that as the brain matures, brain networks change. The brain's overall organization switches from networks involving regions physically close to each other, which is the dominant motif in a child's brain, to networks that connect distant regions, the primary organizational principal in adult brains.

For the new study, lead author Nico Dosenbach, MD, PhD, a pediatric neurology resident at St. Louis Children's Hospital, took this and other distinctions that mark the transition from child to adult brains and adapted them for use in a technique for mathematical analysis called a support vector machine. The technique is employed in many contexts in science and economics and on the Internet.

"It's a way that mathematicians have developed for predicting something with high specificity and sensitivity, when you have huge amounts of data instead of one really good measurement," Dosenbach explained. "Any one of these measurements doesn't tell you much, but if you put them together and use the right math to sift through and restructure them, you can get good predictive results."

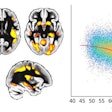

Researchers charted the results of 238 brain maturity analyses, with age on the horizontal axis and maturity on the vertical axis.

Dosenbach used data from five-minute MRI scans of 238 psychologically normal individuals ranging in age from 7 to 30 years. The support vector machine analyzed approximately 13,000 functional brain connections and selected the best 200 to produce a single index of the maturity of each subject. The data allowed the researchers to predict whether subjects were children or adults, and roughly formed a curving line that tracks the path of normal functional brain development.

The researchers suspect that patients with brain disorders will appear out of alignment with this normal developmental curve.

"The beauty of this approach is that it lets you ask what's different in the way that children with autism, for example, are off the normal development curve versus the way children with attention-deficit disorder are off that curve," Schlaggar said.

Schlaggar suggested that functional brain scans might be conducted on children at risk but not yet suffering from a developmental disorder at the same time they are undergoing a regular structural MRI scan.

"When a fraction of these children later develop that disorder, you can go back and construct an analysis like this one that will help predict the characteristics of the next child at highest risk of developing the disorder," he said. "That's very powerful both clinically and from the perspective of understanding the causes of these disorders."

This approach might enable treatment prior to onset of symptoms, Schlaggar says, and should help physicians more quickly and closely track the results of clinical trials of new therapies.

By Cynthia E. Keen

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

September 13, 2010

Related Reading

Quick brain scan could screen for autism, August 11, 2010

fMRI shows PDSD symptoms in kids, December 9, 2010

BOLD fMRI may identify the underlying characteristics of autism, November 10, 2009

MRI spots brain abnormality in autistic children, May 4, 2009

Copyright © 2010 AuntMinnie.com