Philosopher George Santayana, in the Life of Reason, wrote, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." Over nearly three decades as an independent PACS consultant, I have attempted to apply the same common sense in dealing with my customers.

Coming up with just 10 lessons learned for this final edition of Building a Better PACS was nearly impossible. Each time I worked with a client, we both learned something new. Every day was an adventure and, yes, often a challenge as well. But the more you learn the better you become, and the better you become the easier life becomes. Projects that might seem like a monumental task are really fairly simple and just need common sense applied to them.

|

| Michael J. Cannavo |

1. Plan your work, then work your plan

All too often clients tend to take the "ready, fire, aim" approach to project implementation, and it shows. You can't rely on the vendor to do all of the implementation tasks, even though they may say they will do it. This is a team effort and it requires the cooperation of all parties. While you don't need a 1,025-page project plan, you do need to be able to clearly articulate the goals and objectives of the project, so you can measure them against some form of metrics on its success that no doubt administration will request somewhere down the road.

This means you need to define vendor and end-user roles and responsibilities (including those within the organization itself: IT, network, radiology, administration, etc.), a reasonable mutually agreed upon timeline, and other events. A new PACS also doesn't mean you have to throw the baby out with the bath water. Oftentimes much of the existing hardware can be repositioned for use in a backup mode or other application (disaster recovery, for example), saving on hardware costs. Will it run as fast as new hardware? No, but then again more than 99.9% of the time it will sit there idle until it is called upon anyway.

You can also configure systems with dual servers to speed up processing time, using one as a fail-safe/fall-back server in the event the other dies. But it's all about being creative and not overspending. You can do the same thing with a test server in dual roles -- acting as both a test server and disaster recovery server.

2. It's a team decision

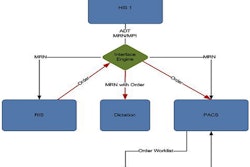

The days of radiology controlling its own destiny are long gone. PACS is being closely looked at as part of an integrated information and image management system that helps make up the clinical patient record. So is a PACS for radiology? Yes and no. Yes, it makes radiology (and radiologists) more productive, but the reality is it makes the primary care physicians more productive, and that is the name of the game.

I won't win any popularity contests by saying this, but radiologists really are not the primary concern of the hospital administration; primary care physicians are. Radiologists are used to getting information to the primary care physicians. If they can do it faster or with greater accuracy, then so much the better. The same can be said with bringing more studies into the facility -- anything that generates more revenue for the facility is a plus. Everyone has a part in the decision-making process here from the chief information officer, administration, IT, materials management, and, yes, even radiology -- but it's a team decision and you can't lose sight of that fact.

3. Do your due diligence

Ignorance is not bliss, yet the reality is, in most cases, that you stand a better chance of making a good decision on your PACS by throwing a dart at a dartboard than by having a facility say it did proper due diligence. PACS is not a mail-order bride and due diligence doesn't end by looking at a quote and selecting a vendor based on price alone.

At an absolute minimum, you need to do onsite workstation demos with the radiologists, but it should never end there. Find a site that is comparable to yours in both application and volume and talk to as many end users as you can. This includes not just radiologists, but the PACS systems administrator, techs, IT and network support staff, key clinicians (if they are available), and as many others as you can gather.

Learn all you can about service; better yet, when you go on a site visit (and you should), have the people you are with initiate a service call and be on speakerphone so you can judge how the vendor handles service. That is crucial. Talk about how upgrades, updates, and billing are handled, and how they work with other vendors (extremely crucial now that PACS and RIS are part of a Health Information Exchange). You can't ask too much, see too much, or hear too much before making a decision.

4. Implement for the present, yet plan for the future

One of the biggest mistakes people make is overconfiguring a system, especially when it comes to the archive. While you need to plan for a minimum of five to seven years of storage, you should only mount two years worth of disks. You can and should also consider cloud solutions where you only pay for as much storage as you use.

Overconfiguring doesn't end at the archive, though. You also need to determine how much power you really need in a workstation. If you are doing advanced image processing including 3D, MIPS, MPR, etc., then it makes sense to get the workstation with dual Hemi headers and a five-speed transmission with overdrive. But if not, why spend the extra money?

The same can even be said for uninterruptable power supplies (UPS). UPS are in place to deal with spikes and surges and allow for a controlled shutdown in the event of a prolonged (more than two-minute) power outage. You don't need a UPS that will keep the system up for two days on batter power. Also keep in mind anything more than 3 kVA requires a 220 V line, which often dictates you running a new separate circuit.

Don't skimp on cooling in the computer room either. If you can't keep it at optimum temperature, then upgrade the HVAC system. And make sure you have a computer room that is, in fact, a computer room. I have seen facilities literally convert janitor closets that had sinks in them as the new computer "room," and then when the drain in the floor that never got covered backed up ... well, you can just imagine. I rarely see systems underconfigured. This doesn't mean it doesn't happen, but often vendors tend to err on the side of caution and put in a lot more than is really needed.

5. It's not about technology

All the technology in the world isn't going to help you if you can't or don't use it properly. It's all about how you use technology to achieve your goals. With meaningful use upon us, every dollar spent needs to be justified, so if a facility can do without something, rest assured it will be cut.

There needs to be a logical reason for buying or replacing PACS, and you need to have your story straight and a logical justification for what you are doing. This is especially crucial with the establishment of vendor neutral archives and use of cloud technology.

Don't get too technical in your justification, but explain how implementing the technology helps meet meaningful use, how funding comes from operating versus capital budgets (a huge plus with administration), how it will reduce IT support requirements (a huge plus with overworked IT departments), and how it will allow connectivity from multiple disparate clinical information systems from multiple disparate sites and vendors -- these things are key.

6. A well-trained PSA is a must

I cannot begin to tell you how many people ignore the requirement to have a PACS systems administrator (PSA) in place. Even a small 20K-volume outpatient imaging center needs someone acting as the PSA, and this should not be the radiologist.

A general rule of thumb is one PSA for every 100K procedures, but the roles and responsibilities the PSA takes plus other clinical systems they support (RIS and transcription among them) may dictate a higher or lower number of PSAs per facility. Regardless of volume, at a minimum you need one full-time PSA, plus a backup in the event of vacations, sick days, or the unlikely event they get hit by a bus.

The words "well-trained" are also important. PSAs not only need to go through the vendor training program, they also should have access to user groups and other PSAs so they can learn about system issues, workarounds, and the like, as well as ways that the systems can be optimized. You don't want your PSA to feel like they are out there all alone, so make sure at least once a year the PSA gets to attend a user group meeting or something like the Society for Imaging Informatics in Medicine (SIIM) meeting, where they can talk shop with fellow users. Finally, always negotiate two people attending the PSA training course and stick to it.

7. Don't be penny wise and pound foolish

You can get PACS for free or spend a small fortune, but nowhere have the words "you get what you pay for" been shown truer than with PACS. You really need to look at the value you are getting, not just the cost.

How many sites like yours have they implemented? If it's not many, you can bet there is a reason unless it is a brand new company. How many updates and upgrades do you get annually and how often do you see these? This often tells you about the depth of their software development team. When you call late at night, are you getting someone answering the phone who can address your problem in real-time or an answering service for somebody who's covering service remotely?

8. Having a good contract is crucial

I have been over this point ad nauseum, but vendor contracts typically do very little to protect the end user. Therefore, you need to have a good addendum to the vendor contract that protects those needs. This should include things like an errors-and-omissions clause, roles and responsibilities, a detailed description of the system operation from a workflow standpoint, and a payment schedule predicated on meeting system performance parameters with at least 20% held back for clinical acceptance. You also need to clearly agree upon on what constitutes clinical acceptance. I like to use the following language, but you can use any analogue therein:

Clinical acceptance shall be defined as the system installed and operational per the specifications, appendices, and other information described by (the vendor) in writing and against which this award is based. (The end user) shall be responsible for reviewing system operation and certifying that the system is as specified in discussions and subsequent contract award. (The vendor) shall be responsible for insuring that the product reflects what was represented in the quotation and subsequent discussions, in product specifications and/or brochures, and that it can meet the defined system performance specifications.

Vendors will often say that this is all covered in the project plan, but the project plan is typically not part of the contract, so don't fall for that. If it is indeed covered by the project plan, then make the project plan part of the contract; it's that simple. Understand, too, that a lot of vendors and especially the majors will not include any form of penalties for nonperformance due to revenue recognition issues, so you may be hard pressed to have a vendor compromise in this area. Those that do agree to penalties typically have the penalties so couched that you'll rarely, if ever, see any financial reimbursement.

9. Don't go it alone

None of us is as smart of all of us, yet time and again I see the classic definition of insanity playing itself out in this marketplace. "We did our own RFP before, and we will use the same one again." In the words of Dr. Phil, "So, how's that working out for you?" Your first system implementation was a nightmare because you had no clue what to tell the vendor you wanted or needed, and they didn't know what questions to ask of you either.

As a consequence, you got a system that marginally performed and that everyone hated. You hung on to it until the end of its useful life, so you could use the exact same process to buy a replacement system. "It's working just fine, Dr Phil."

Nearly half of my end-user business last year came from clients who made a bad PACS decision and needed help getting out of the deal. I was successful in helping these clients, but you typically use contraception before you get into bed, not after. While a good contract can serve as a morning-after pill for a bad PACS decision, more often than not, you are going to be stuck raising a baby you really didn't want to have -- so for everyone's sake, get qualified help, with an emphasis on the word qualified.

10. Vendors are not always the enemy

A good vendor will work alongside you from the first day you meet to discuss their system until the day you migrate off it, and even beyond, so it is important that choose the vendor like you would a spouse. Just like being married it's important to nurture the relationship, to overlook minor irritants that we all have, and to look at the bigger picture.

That said, you also need to know when it's time to cut your losses and move on. It's appalling to me that 75% to 80% of all replacement PACS choose another vendor when it should be 20% to 25% at best. Part of this could be unrealistic expectations an end user has for the system or vendor, but frankly, it's the vendor's responsibility to set and maintain the expectations, and obviously this isn't being done properly. The seven-year itch lives in PACS just as it does in marriage, but when you have an itch you need to scratch, well ...

After 28 years, I too had an itch I needed to scratch and am moving out of the role of an independent consultant and into a role where I can help a lot more facilities with the knowledge I have accrued over the years. Yes, I will be working with a major vendor, but it's a vendor I implicitly trust, whose integrity is a cornerstone of the way they do business, and whose product, while not perfect, is close enough that I can promote it and still sleep at night (unlike my last foray into the commercial world way back in 1984).

And don't worry. While I may take a sip of Kool Aid now and then, I'll make sure that I know the person giving it to me and not have it be Reverend Jim Jones. The future is exciting for us both. It's been a pleasure being the PACSman and sharing with you all. Until we meet again, God speed and God bless.

Michael J. Cannavo is a leading PACS consultant and has authored nearly 300 articles on PACS technology in the past 16 years. He can be reached via e-mail at [email protected].

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnie.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular vendor, analyst, industry consultant, or consulting group. Rather, they should be taken as the personal observations of a guy who has, by his own account, been in this industry way too long.