If you're a developer of imaging informatics software, does the thought of navigating the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) regulatory review process fill you with abject terror? If so, then maybe you should update your perspective of the agency.

FDA officials offered tips for making the regulatory review process easier at a session of the Society for Imaging Informatics in Medicine (SIIM) annual meeting earlier this month. In addition to some new regulatory procedures for imaging informatics products, the agency is also touting a new, more flexible attitude that should be a refreshing change for many developers.

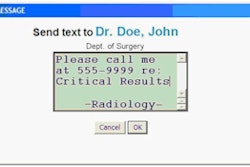

Mary Pastel, PhD, director of the division of radiological devices at the FDA's Center for Devices and Radiological Health, and Elizabeth Krupinski, PhD, professor and vice chair of research in radiology at the University of Arizona, starred in a skit to explain the process.

Playing the role of an imaging informatics inventor with great ideas but shallow pockets, Krupinski's first new product ideas fit FDA requirements for a classification with the lowest risk, class I. This was a plug-in application designed to transparently assess the productivity of a radiologist by measuring how many cases are read in a defined time period, how many reports are generated, how many images each case has, and how long it takes to interpret a specific type of exam.

The FDA classifies new products based on intended use and the risk level to both a patient and the device operator. FDA requirements for class I include registration and listing, the use of good manufacturing practices, accurate and nondeceptive labeling, detailed recordkeeping, and reporting of device failures. A class I product may or may not require a 510(k) premarket notification.

Krupinski's second new product idea, an app for a mobile tablet or smartphone to display CT and MRI exams, could be classified as either class I or class II, depending on its application. If it's used only to display images that have already undergone diagnostic review, it would be a class I device. If the software was marketed and labeled for use as a diagnostic display, it would move into class II.

Class II devices are subject to special controls to minimize risk, in addition to general control requirements. These include special labeling and guaranteed performance requirements, postmarket surveillance, and tracking and adherence to guidelines and guidance. A 510(k) clearance is mandatory.

"The key to getting clearance is to demonstrate that your device is substantially equivalent in terms of usage, safety, and effectiveness to a product that is already on the market," Pastel explained. "It must have the same technological characteristics or differences that do not raise different questions relating to its safety and effectiveness. Ideally, the process is supposed to take 90 days."

The FDA receives few applications for products that receive a class III designation. These are usually devices that support or sustain human life, are of substantial importance in preventing impairment of human health, or which present a potential, unreasonable risk of illness or injury. Premarket approval (PMA) requirements are stringent, and the review process is considerably longer, a 180-day review.

"The cost is also considerably more expensive," Pastel said. "Fees alone to the FDA increase by a factor of 10. Clinical trials are more complex. There will be panel review. The cost to receive FDA approval for most class III devices is at least $10 million."

Products with no identifiable predicate devices, or substantial equivalents in the market that are of low risk, may qualify for the FDA's "de novo" process. The de novo process provides a possible route to market by allowing an applicant who has received a "not substantially equivalent" (NSE) letter from the FDA to request a risk-based classification determination to be made for the device. This process should take approximately 60 days.

Approximately 5% to 7% of products are designated as being not substantially equivalent, according to Pastel. She said that her division sends an "additional information" (AI) request letter, and that there may be several rounds of requesting and receiving information before a decision is made.

Pastel strongly recommended that any potential applicant have a pre-IDE (investigational device exemption) meeting with the FDA. The meeting may be conducted in person, through videoconferencing, by telephone, or with email exchanges. It is a free-of-charge venue in which an inventor or company may informally discuss the characteristics of the product and its intended use. Informal determinations can be made as to which classification category the product will be assigned, and what substantially equivalent products have already been approved by the FDA.

The process is straightforward. It's necessary to send a request that includes a description of the device and the topics that the applicant wishes to discuss.

"Pre-IDE discussions are most frequently used to discuss the specifics of a clinical study," Pastel said. "We don't want you to undertake an expensive study when you don't need to do so."

Follow the FDA's advice

Pastel strongly counseled applicants to follow the FDA guidance on the regulatory process.

"When you share details of how a device works and what you want to use it for, the best thing to do is to follow our advice," she said. "A lot of companies have discussions with us, and we give them advice that they don't follow. Often this has to do with the clinical studies they undergo. There are a lot of ways to mess up a clinical study, often caused by introducing clear biases."

She also noted that companies or inventors may make the mistake of undersizing or oversizing a clinical study, which add to the cost of getting a product approved.

In Krupinski's hypothetical case of a mobile diagnostic display viewer, following recommendations from her pre-IDE meeting with Pastel and her staff, she would design and conduct performance testing and a clinical study, if recommended.

She has the option to select who participates in the study -- it may be her own colleagues -- using images of her own choice. The FDA wants proof that images were reviewed by qualified experts who found that the images displayed on the viewer were sufficiently acceptable for diagnostic use, Pastel explained.

"We are seeking clinical justification by experts whom we can track down and talk with," she said. "There are also occasions when we will ask for the device and the set of images used to perform laboratory validation ourselves."

The FDA does not give applicants recommendations on medical experts, including medical physicists and statisticians, because this could be a conflict of interest. But Pastel acknowledged that identifying experts could be a real barrier to a solo inventor.

It's up to the applicant to "make the case" for the product. The applicant develops the categories and content of comparison tables and models performance testing that is comparable to the predicate device. In the case of a mobile diagnostic viewer, in addition to meeting the basic requirements mandated for any medical display, it should also be assessed in a variety of reading environments and different lighting conditions.

The applicant determines the conditions in which the device is safe to use. Images that are diagnostically acceptable in a reading room may be totally unacceptable when viewed on a golf course, but it's up to the applicant to establish the parameters of use, Pastel explained. "We either agree with you or disagree," she said.

The FDA website contains a 510(k) summary of safety and effectiveness for every cleared or approved product, and this provides a model to follow for an applicant with a predicate device. It represents a snapshot of the material submitted, which may be as few as 50 pages -- up to 23 volumes of several hundred pages each.

When the FDA has questions, the "clock" is stopped for a defined "reasonable" period of time. "We try to work interactively," Pastel said. "We call you to discuss the questions that we have and additional material that we need."

Because presentations may need to be made at FDA headquarters before a panel of experts for a class III device and on occasion for a class II device, Krupinski expressed concern that proprietary information may be disclosed.

"Are competitors allowed to attend the open sessions?" she asked. Pastel responded that they are and they do. But she also stated that any proprietary information is kept confidential, and a hearing would be closed when proprietary information was discussed.

Questions from the audience

If a radiologist has developed software that he or she uses for diagnostic assessment, does it require clearance? As long as it isn't sold, this usage is considered to be "the practice of medicine" and is outside the purview of FDA regulation.

Similarly, a "home-grown" RIS or PACS developed by a hospital or radiology practice for internal use only is exempt because it is not being developed for commercial sale.

Switching hardware platforms may or may not require a new product submission. The same is true for software updates. The FDA has guidelines, and it's the device manufacturer's call to determine whether changes have exceeded the boundaries requiring a new clearance submission. If uncertain, contact the FDA to find out.

All consultants retained need to be identified, and they also need to be accessible for questioning by the FDA. This may incur additional costs to an applicant.

Does the FDA care how an applicant gets information about a predicate device? No. "You may obtain predicate information if it is published on the summary documents of products that are already cleared. You can also buy, rent, borrow, or steal a competitive device if information is not available to make your comparison," Pastel said. "Don't forget that competitor's websites, exhibition booths, and published articles may be excellent sources of information."

To bring a product to market, consider an intended use that will allow for the lowest classification. Intended use can drive a product into different classes. "You can come back later after you have had more experience and market penetration to change the intended use," she said.

Products with new features and new functionality probably will be substantially equivalent in use to predicate devices. Pastel said that the FDA expects imaging informatics inventors to develop products with unique characteristics, but the mindset of the inventors should be to identify their product with a predicate device that has already cleared the hurdles.

The FDA now tries to have the same reviewer assigned to a product during the duration of its application. If reviewers do not have the expertise required, they are expected to obtain assistance from a pool of agency and consultant experts that include physician specialists, engineers, medical physicists, and statisticians, among others.

To the participant who admitted that his organization was very creative but had a "hesitancy that borders on abject terror of submitting anything to the FDA," Pastel's response was "talk to us. The FDA talks really tough but is now more flexible than it used to be."

These were encouraging words for a room filled with creative people.