Stroke, the third-leading cause of death in the U.S. and one of the primary causes of long-term disability worldwide, has found its sales team. Type "stroke center" into Google and you'll get more than 20 million hits. It looks so easy -- could one of them be your next business venture?

Better think about it long and hard, and plan to hire a lot of talented people, cautions a stroke specialist from Germany. Peering through a glass half full might reveal 20 million ways in which a mini stroke center could get you in trouble.

"Just buying a machine and training a neurologist to look at images isn't enough for a real stroke center," said Dr. Michael Forsting in a presentation at the 2007 European Congress of Radiology (ECR) in Vienna.

Forsting ought to know. As head of the Central Institute for Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology and Neuroradiology at the University Clinic in Essen, Germany, he's seen too many cases that required highly specialized skills and would have been undertreated, often dangerously so, at a bare-bones facility. And even in large centers, complex cases don't confine themselves to workdays.

"The first thing that you obviously need are (scanning) machines, but if you're going to have a stroke center you need manpower," Forsting said. "You need people on call who cannot only scan and look at images but can also treat patients, and not only treat ischemic stroke but treat hemorrhagic stroke as well. My team is womanpower -- four women who can treat AVMs (arteriovenous malformations) who can treat aneurysms even on Christmas night -- this is absolutely necessary."

And since people don't work 24/7 even when it's not Christmas, "it's not enough to have one expert for something; you need at least three to four people who can do everything," he said. "You need neurology, you need neurosurgery, you need ICU. There is much more emergency action necessary than sometimes thought. Because stroke is not only ischemic stroke, there is hemorrhagic stroke. Lots of people come to stroke centers and they suffer from hemorrhages and ruptured aneurysms."

Intervascular interventions are very complex, and they should be done in larger centers only, Forsting said.

Imaging, on the other hand, is but one component of stroke radiology, he noted.

It is a valuable one, of course. Radiology ensures the proper reading of CT and MR exams. Diagnostic imaging can be done in small work units, and with the aid of teleradiology, images can be read far from where they are acquired.

When imaging confirms severe acute ischemic stroke, intra-arterial therapy is increasingly common for patients these days, many of whom present after the three-hour window for symptom onset, Forsting said. Using posterior circulation as a kind of time line, "we will use a catheter recanalization more and more and more with these patients, because we can dramatically reduce risk of hemorrhage and dramatically increase the benefit to the patient," he said.

Thrombotic stroke and TIA

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) differs from a full-blown stroke in that the blood flow interruption to the brain is only temporary. They don't kill brain cells or result in permanent brain damage in and of themselves. However, TIA patients have more than a 10% chance of becoming stroke patients.

These days TIAs are getting more attention. U.S.-based TIA centers are advertising on the Web, and a few are opening in Europe, Forsting said.

"Patients presenting with TIA are at tremendous risk of developing stroke the (same) day," he said. "TIA is the most important risk factor for new stroke; the highest risk is 24 hours after (TIA) onset. And radiology will play a key role in the diagnostic workup of these patients -- again you have to have high expertise."

Preventing TIA from becoming a full-blown stroke requires a broader focus than simply imaging the brain, Forsting said.

"We have heard of many patients who have suffered from embolic stroke ... that is not restricted to the carotids or intracranial arteries," he said. "So even if we are purely radiologists, we have to learn to image the heart -- and it's not too difficult."

Looking at the heart will help the radiologist look for embolic sources, such as a clot attached to the aortic arch, and determine whether the patient is at high risk of developing a stroke in the next 24 hours, Forsting said.

"TIA centers really force us to do more than the brain, more than the cerebral vessels, more than supraaortic vessels," he said. "We have to do the aortic arch and we have to learn how to image the heart."

ICH skills

Then there is intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), which accounts for 10% to 15% of all strokes. ICH is the least treatable form of stroke and associated with a high mortality rate. The diagnostic workup is fairly straightforward with MRI or CT, Forsting said. But it doesn't end there.

After imaging, "we have to do the etiologic workup -- and sometimes this is immediately required," he said. "And sometimes (ICH) requires immediate emergency endovascular treatment."

In most patients the hemorrhage is arterial in origin; venous congestion is less common. "And the etiology is hypertension in the vast majority of patients, but then there are vascular malformations and aneurysms and both sometimes need emergency treatment," Forsting said.

Small centers can handle a small ICH pretty easily, he said, because patients don't need endovascular treatment. But if imaging shows signs of venous thrombosis, then the patient needs catheterization despite the presence of cerebral hemorrhage.

"Catheterization can save the lives of patients with signs of venous thrombosis," Forsting said.

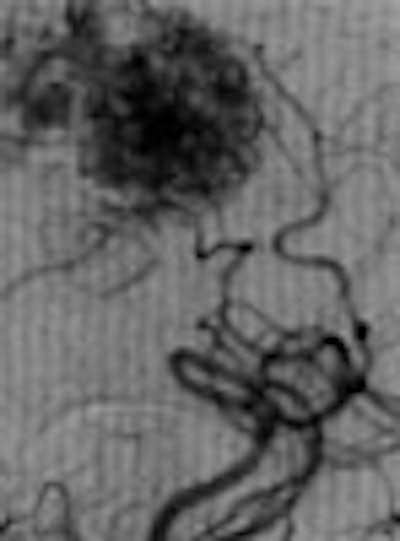

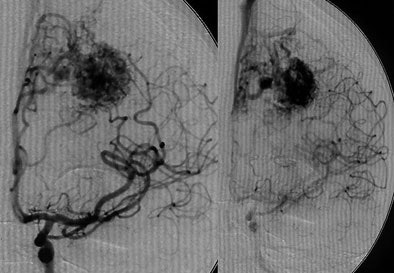

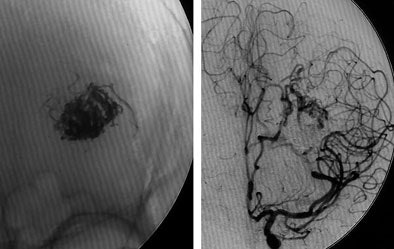

In one ICH case, a patient did not present with typical hypertensive etiology, he said. Angiography showed an occluded AVM of the middle cerebral artery, and "these patients do need endovascular treatment," he noted. "These are not patients for small stroke centers. You need experienced teams to do endovascular therapy because we can now cure 50% of patients without surgery and without radiation therapy."

|

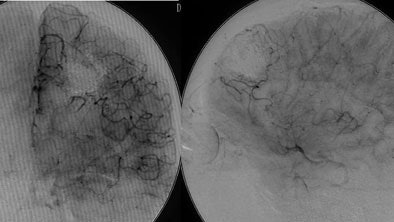

| Digital subtraction angiography shows arteriovenous malformation at presentation (top, below) and two weeks postembolization (bottom) with endovascular administration of ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer embolization agent (Onyx, Micro Therapeutics, Irvine, CA). The patient had repetitive transient ischemia attacks due to cerebral steal from the AVM. Images courtesy of Dr. Michael Forsting. |

|

|

In another example, a patient with an AVM located in the speech center of the patient's brain was a "No-touch AVM" for the neurosurgeon if not the endovascular therapist, according to Forsting. "We know these are pretty dangerous," he said. "Nowadays we go in with a catheter and we can occlude them completely." Late-venous-phase CT three weeks later showed complete occlusion, and the patient suffered no neurologic deficit.

The risk of surgery is largely dependent on the size of the AVM, Forsting said. A large AVM brings a 50% risk, which is reduced tenfold for smaller AVMs.

"Endovascular therapy is mandatory in all patients with AVM, and you need to treat all patients with AVM," he said. A 2002 study by Simon et al examined the long-term outcomes of patients with intrinsic brain AVM. Over an average 10 years of follow-up, conservative management produced a 24.6% mortality rate, while active management reduced mortality and morbidity to 3.9% (p = 0.031), Forsting said (Stroke, December 2002, Vol. 33, pp. 2794).

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), or bleeding into the subarachnoid space around the brain, makes for a pretty straightforward diagnosis on MRI or CT, Forsting said. Some patients have ischemic stroke symptoms as a result of "rebleeding when they didn't realize the first bleeding," he said, with intracranial aneurysm rupture presenting as a delayed stroke secondary to cerebral vasospasm. The endovascular therapist can enter and use one of several methods to completely occlude the aneurysm.

A patient presenting with stroke symptoms due to brain stem compression is another emergency situation that a small stroke center is not equipped to handle, and there are myriad other examples, he said.

"I think mechanical recanalization must be part of the endovascular repertoire, and will be increasingly part of treating patients with ischemic stroke because we can really dramatically reduce risk of hemorrhagic transformation," Forsting said. AVMs need urgent diagnosis but rarely emergency treatment, while ruptured aneurysms do need emergency treatment, he concluded.

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

April 25, 2007

Related Reading

Occlusion site influences thrombolysis success, March 23, 2007

Intracranial hemorrhage rate low with intra-arterial thrombolysis for stroke, March 21, 2007

CT spot sign predicts hematoma expansion in stroke patients, February 26, 2007

Mechanical clot removal can often improve stroke outcomes, February 13, 2007

Advanced MR clarifies nexus between white matter and cerebrovascular disease, February 9, 2007

Relative threshold method correlates CT, MRI stroke infarct assessment, February 9, 2007

Copyright © 2007 AuntMinnie.com